| Year | Arab | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 3691 | |

| 1944/45 | 6730 | 6730 |

| Year | Arab | Jewish | Public | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1944/45 | 5633 | 885 | 264 | 6782 |

| Use | Arab | Jewish | Public | Total | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

144 | 36 | 264 | 444 (7%) | ||||||||||||||||

|

5489 | 849 | 6338 (93%) |

The village stood on flat terrain on the central coastal plain, on the north side of a highway leading to Jaffa. The inhabitants believed that their village was named after Salama Abu Hashim, a companion of the Prophet Muhammad, who was buried in the village in A.D. 634. His tomb, on the northwest side of the village, became known as the shrine of Sayyiduna (our master) Salama.

In 1596, Salama was a village in the nahiya of Ramla (liwa' of Gaza) with a population of ninety-four. It paid taxes on a number of crops, including wheat and barley, as well as on other types of property such as goats and beehives.

The Syrian Sufi traveller al-Bakri al-Siddiqi, who traveled in the area in the mid-eighteenth century, visited the above-mentioned shrine.

In the late nineteenth century, Salama was a village built of adobe brick and had a few gardens and wells.

During the British Mandate, Salama was divided into quarters, each quarter inhabited by a hamula (clan) or sub-clan. The houses were at first clustered together, with the houses of each hamula or sub-hamula centered around a large courtyard (hawsh) that had a single common entrance. The courtyard provided private space for women to do their household chores, for children to play, and for families to gather in the evening or on special occasions. Some families also built houses in the orchards; these did not usually belong to hamulas. Although most houses were constructed of adobe brick, some people built stone houses and Baghdadi houses, which were made of wood and insulated with gravel and whitewash on the inside. The population was comprised of 6,670 Muslims and 60 Christians. Salama had two elementary schools, one for boys and another for girls. The boys' school was opened in 1920 and the girls' in 1936; 504 boys and 121 girls were enrolled in 1941. The villagers also supported a soccer team.

There were numerous shops in the village, including five coffee shops. During the Mandate, a transportation company that owned cars and buses was established in Salama, with partners from the neighboring village of al-'Abbasiyya; the company was called the Salama–al-'Abbasiyya Automobile Company. The villagers worked primarily in agriculture and associated activities, and to a much lesser extent in commerce and the civil service. In 1944/45 a total of 2,853 dunums was devoted to citrus and bananas and 2,266 dunums were allocated to cereals; 370 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards. Agriculture was both rainfed and irrigated; irrigation water was drawn from some eighty-five artesian wells.

The residents shipped their produce in Jaffa and sold some of it in nearby Zionist settlements. They also shipped milk to a dairy factory in Jaffa that was owned by two men from Salama.

Salama was hemmed in by a number of Jewish settlements and came under almost continuous attack for a period of five months, beginning on 5 December 1947, a week after the passing of the United Nations Partition Resolution. The New York Times reported that members of the Haganah opened fire with machine-guns at Salama on that date and that Arab families were evacuating the area and moving towards Ramla and Lydda. The Palestinian newspaper Filastin reported a two-pronged attack on the same date, which abated when British police arrived and later resumed during the night. Sniping and further attacks were reported over the following two days. The History of the Haganah states that in December 1947 'the Haganah leadership in Tel Aviv decided to attack the infamous village of Salama,' adding that 'this was the first attack on an Arab village.' The assault was carried out at dawn on 19 December and was unsuccessful. Palestinian historian 'Arif al-'Arif mentions another raid on 28 December and writes that it was preceded by a diversionary attack from the settlement of Petach Tiqwa. The raid originated at Ramat Gan, where the Zionists had assembled a large force drawn from the Jewish Settlement Police and the Irgun Zvai Leumi (IZL). The village's defenders managed not only to drive the attackers back, but mounted a counteroffensive against Petach Tiqwa, where they were joined by militiamen from Lydda and al-'Abbasiyya.

In early January 1948, the villagers had set up various makeshift defenses around Salama. The New York Times reported on 11 January that British army units had used gunfire to clear four roadblocks around the village and had told the mukhtar to make the people fill in a large ditch 'presumably intended as a defense measure.' Filastin described the same incident, adding that the army justified its actions by saying that it needed to move freely through the area. The defensive barriers were evidently being put to good use, since Filastin reported no less than ten separate attacks on the village in the month of January alone, sometimes more than one in a single night.

The Zionists believed that Salama provided shelter for nonlocal guerrillas, but al-'Arif writes that it was the villagers themselves who organized a militia of around 30 men, in the wake of the UN Partition Resolution in November 1947. After that, scarcely a day went by without a skirmish around the village, during which 'bullets rained down' upon Salama. On 18 January 1948, Israeli historian Benny Morris records a major Zionist attack on the village, by the Third Battalion of the Alexandroni Brigade. The operational orders for the January operation stated: 'The aim is… to attack the northern part of the village of Salama … to cause deaths, blow up houses and to burn everything possible.' A qualification was added: 'Efforts should be made to avoid harming women and children.' According to Morris, numerous houses were destroyed in the January attack.

The largest attacks that occurred in subsequent weeks and which were reported by various sources were carried out on 28 February and 15–16 April. The Arab Liberation Army sent 20 fighters to join in the defense of Salama during the first attack. Reporting on that attack, the New York Times indicated that the Haganah had 'invaded' Salama, and the attack was only revealed the following day when British police discovered the bodies of 6 Jews killed during the attempted invasion. A communiqué issued by Arab militia forces based in the area said that a force of 250 Jewish troops participated in the first attack, including an advance party of 50. It added that the 6 Jews killed were part of the latter force, which was surrounded by the village's defenders. The communiqué, published in Filastin, said that 3 Arabs were also killed in the battle, including 1 woman. In the second attack, al-'Arif writes, at least 30 three-inch mortar shells rained down on the village from Jewish positions at Petach Tiqwa.

The attacks persisted into the second half of April, but the village defenders soon ran out of ammunition, and the residents began to leave. The village was not occupied, however, until the end of April, during Operation Hametz ('Passover'; see Bayt Dajan, Jaffa sub-disctrict) which aimed at the encirclement and occupation of Jaffa. Units of the Alexandroni Brigade occupied Salama on 29 April 1948.

Morris quotes the Haganah radio as saying that the village was evacuated 'at the first onslaught,' but al-'Arif states that Jewish forces did not enter Salama until they had made sure that it had been evacuated by its residents. Al-'Arif writes that the village was empty by 30 April, and a Times dispatch indicates that Salama surrendered to the Haganah on that day. Later that day, Salama was visited by Jewish Agency chairman David Ben-Gurion, who wrote in his diary that he found 'only one old blind woman.' Morris states that the villagers were scattered among various locations, some going to the Ramallah and Nablus areas, others to Gaza and Jordan.

The village and its lands have been engulfed by the expansion of Tel Aviv.

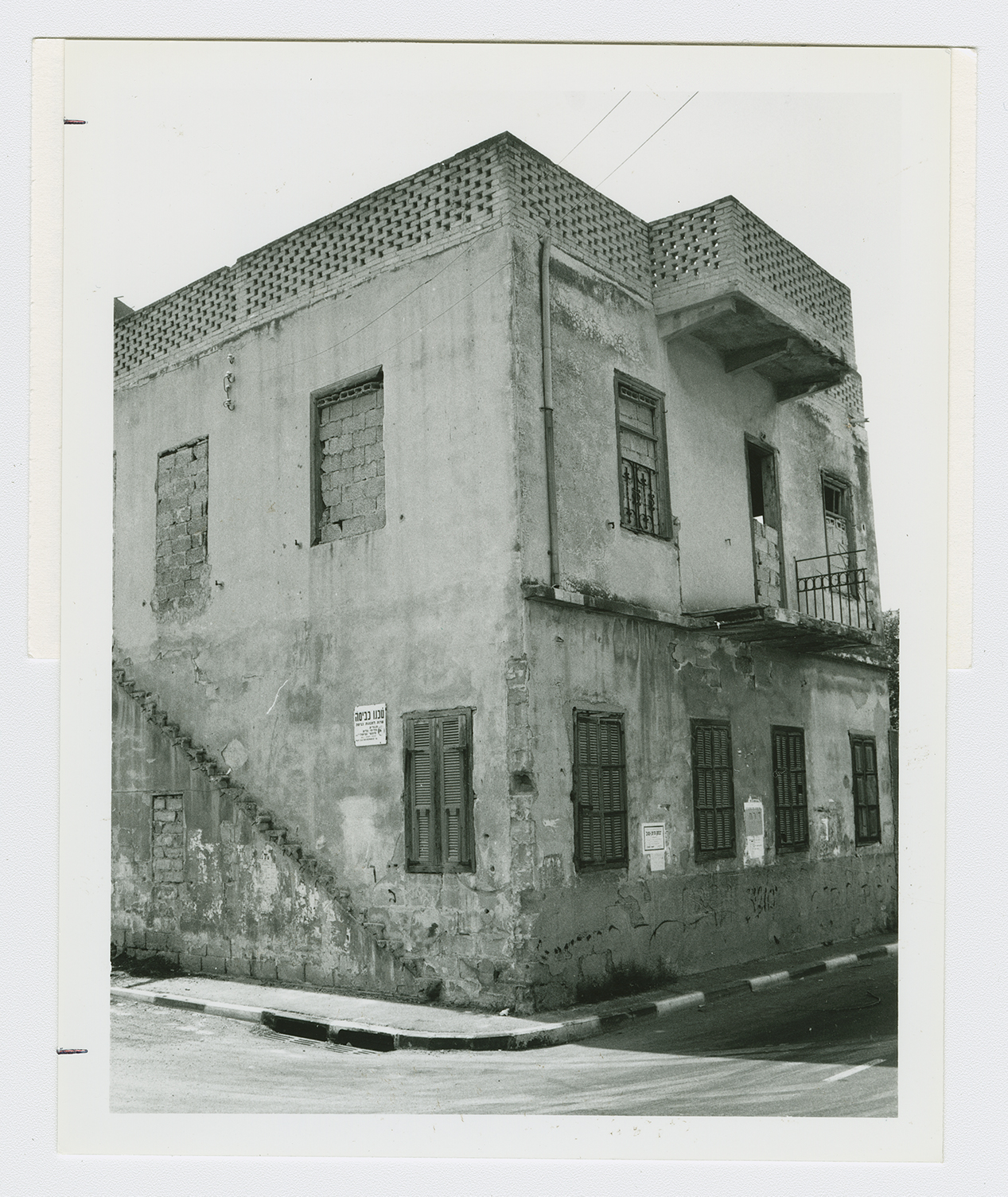

A number of village buildings remain: numerous houses, four coffee shops, the mosque, the shrine, one cemetery, and the two schools (see photos). The houses are deserted and in a state of disrepair, except for a few that are inhabited by Jewish families. Most are made of concrete and exhibit a variety of architectural features. They are either one- or two-storey buildings and have rectangular doors and windows (except for one that combines both arched and rectangular windows). Four houses are identified as belonging to Ahmad Muhammad Salih, Mustafa Abu Najm, Abu Jarada, and Abu 'Amasha. The house of Abu Najm is a two-storey, concrete structure with rectangular doors and windows (some of which have grillwork and others shutters). It is sealed, and the outside staircase leading to its second floor is gone.

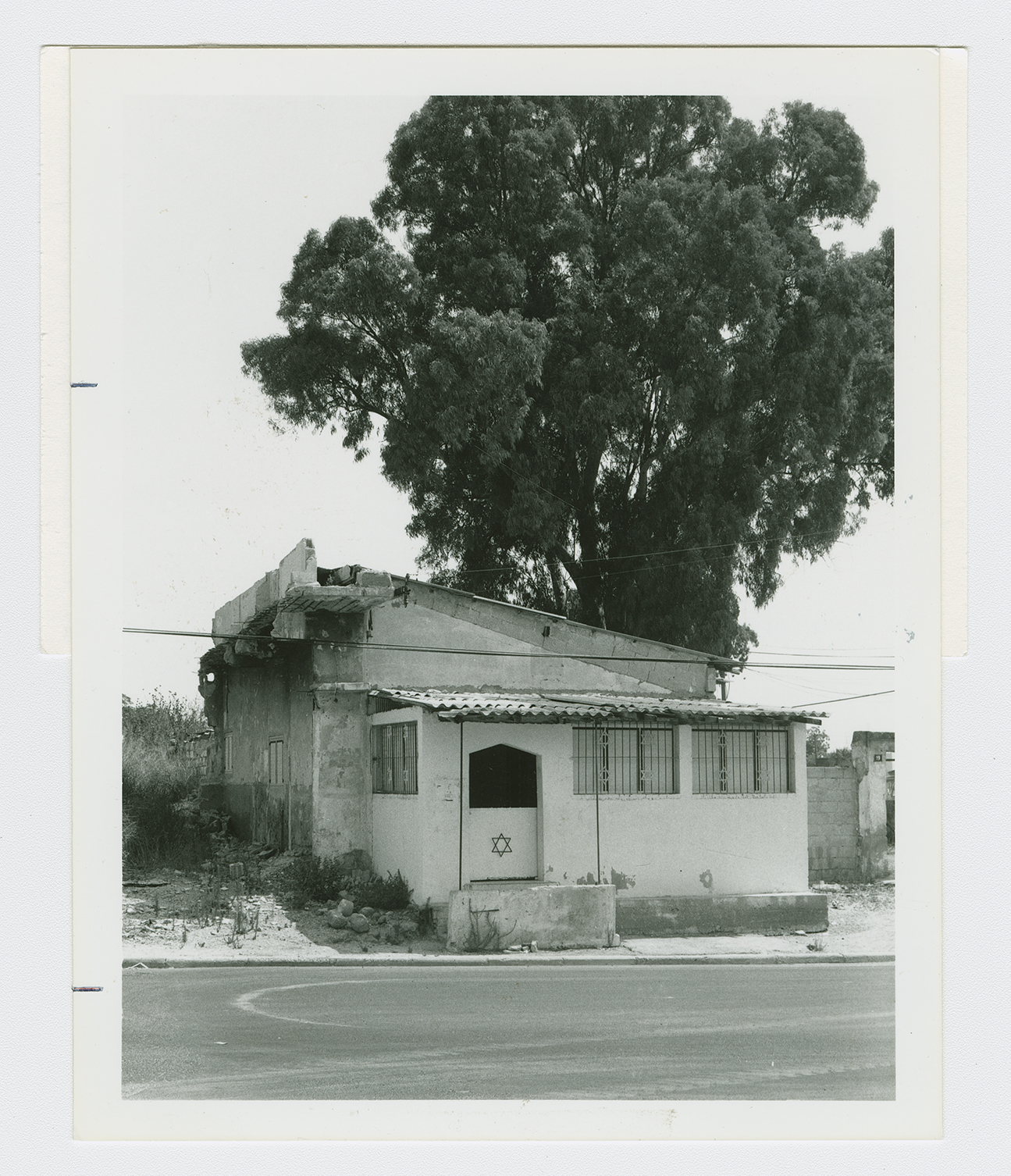

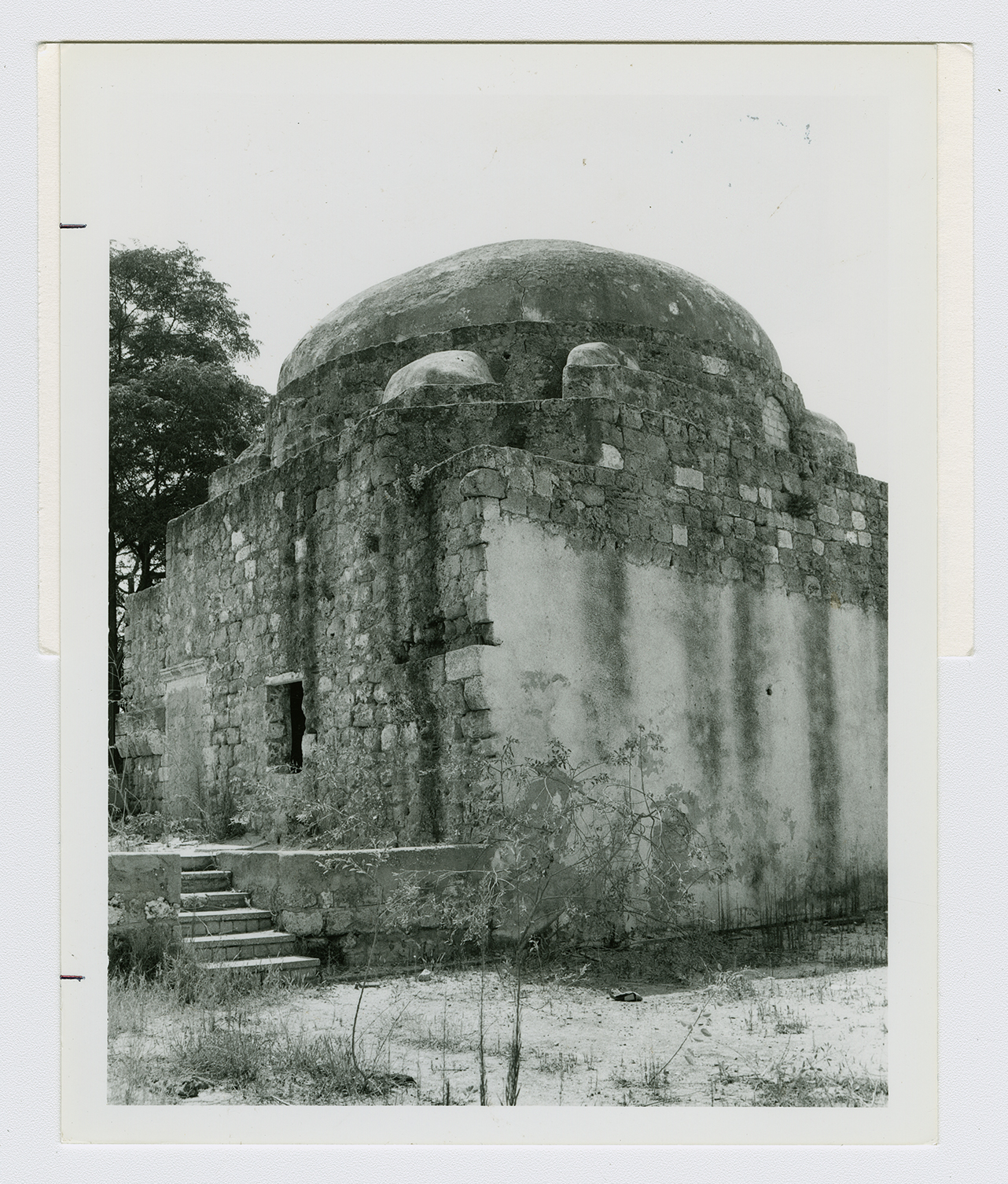

The four coffee shops were named after their owners: Muhammad al-Hawtari, Abu 'Asba, Sha'ban al-Naji, and al-'Arbid. A Jewish family lives in the al-Hawtari coffeeshop. It has an enclosed front porch and a slanted roof covered with corrugated metal sheets; the bottom door panel has been marked with a star of David. The domed shrine is in a state of disrepair. One of the two village cemeteries ("the martyr's cemetery") is deserted and overgrown with wild vegetation, while the other has been turned into a small Israeli park. Fig, cypress, palm, and Christ's-thorn trees and cactuses grow on the site. The surrounding land is generally covered by construction.

Related Content

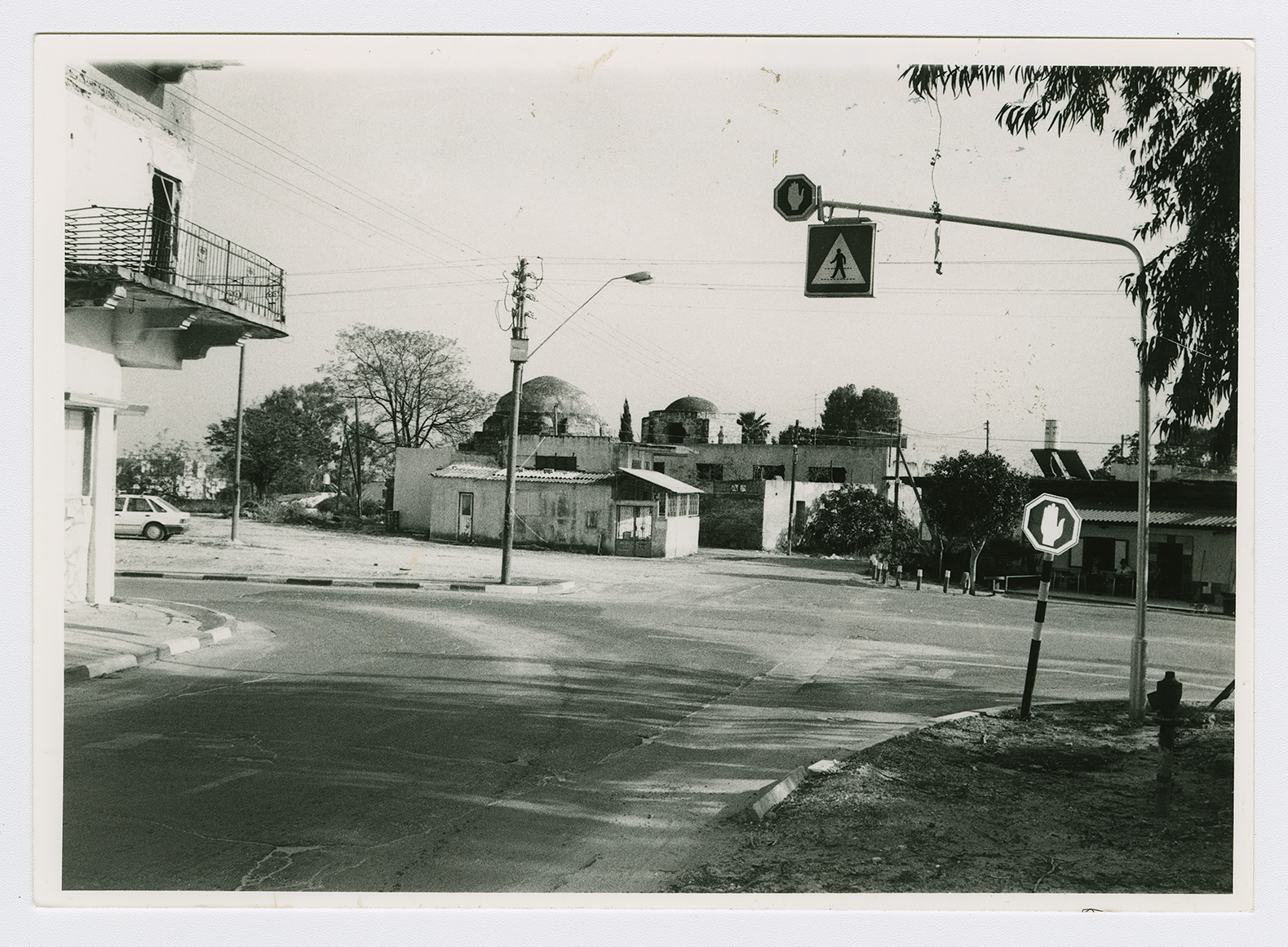

Houses in the middle of the village site. A suburb of Tel Aviv is visible in the background.

The coffeeshop of Sha'ban al-Naji.

Domes of two village buildings, viewed from the center of the site looking south. The dome on the left belongs to the shrine of Sayyidna Salama.

The al-Hawtari coffeeshop, now inhabited by a Jewish family.

The shrine of Sayyidna Salama, after whom the village was named.

The house of Mustafa Abu Najm.

The cemetery of Salama, now a park.