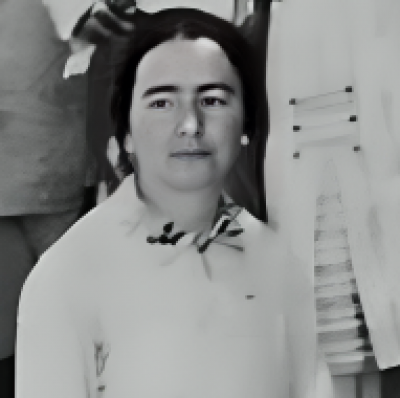

Sophie Halaby

صوفي حلبي

Sophie Halaby was born in Jerusalem on 26 June 1905. She was the daughter of Jiryes Nicola Halaby and Olga Fanahud. She had an older brother, Nicola, and a younger sister, Anastasia (Asia).

The Halaby family moved from Jerusalem to Kiev in 1914. With the outbreak of war between the Ottoman and Russian empires, the family feared that Olga, a Russian national, would be subjected to persecution by the Ottoman authorities.

Halaby began elementary school in Kiev. The family returned to Jerusalem in 1917, and she was enrolled at the English Girl’s High School of Jerusalem which was founded by Protestant missionary Mabel Clarisse Warburton. The school was renamed Jerusalem Girls’ College (JGC) in 1922.

Sophie Halaby grew up in a highly educated family; her father was a well-educated dragoman to the Russian Church, and her mother was a teacher. Her affiliation with the English School opened up the opportunity to grow up in a multicultural and multilingual environment. At school her art talent was noted and encouraged. She graduated from school in 1924, with a high school diploma, and mastery of four languages: Arabic, English, Russian, and French.

After her graduation, Sophie worked with the British Mandate administration in Jerusalem. During that period, she successfully passed the Cambridge Oxford Matriculation exam, but she was never nominated for a promotion. She and other Palestinian Arab employees experienced discrimination and prejudice manifested in unequal payment and lack of promotions compared with their British counterparts.

Halaby was part of the vibrant cultural scene in Jerusalem between 1924 and 1929. She attended events, lectures, and exhibitions that were held mainly at the YMCA. She also attended book club meetings held by the Jerusalem Girls’ College alumnae. During that period, she met Russian artist George Aleeff who had immigrated and resided in Jerusalem. Her interaction with Aleeff and other international artists who had settled in Jerusalem opened up opportunities to foster novel artistic tools and skills. Aleeff focused on the natural and architectural landscapes and day-to-day life in Jerusalem. His works significantly impacted her art and triggered her interest in Impressionism.

Art School in Paris

After having spent four years working for the Mandate administration, Halaby quit her job in 1928 to pursue a career in art. In 1929, she earned a scholarship from the French consulate in Jerusalem to study visual arts in Paris. The scholarship program was initiated by French consul Jacques d’Aumale for high school graduates, and Halaby was among the first Arab women to receive this scholarship.

In Paris, Halaby resided at the Foyer international Foyer des étudiantes in rue Saint Michel. The residence served as a hub for artists and intellectuals to interact and exchange their ideas about art and culture. She was able to network with international artists and discover their works at a time when Europe was witnessing radical transformations in the visual arts scene. During her stay in Paris, she exhibited her paintings at the Salon des Tuileries which was renowned for hosting avant-garde artists whose works did not draw the attention of mainstream galleries and exhibitions. She exhibited four works in 1932: Palestine; Jerusalem; Un Coin de Montparnasse; and Nature Morte, and in 1933, she exhibited Fleurs and Nature Morte. In that same year, she earned a prize from the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris for her work Portrait d’une femme.

Political Cartoons

Upon finishing her studies in Paris, Halaby returned to Jerusalem just before the outbreak of 1936 Great Arab Revolt. She accepted a teaching post at Schmidt's Girls College, and engaged with the national resistance together with students and alumnae from Jerusalem Girls’ College (JGC).

Halaby published eight political cartoons addressed to the British government against the politics of the Mandate in the bilingual Palestine and Transjordan: Weekly Review of Political, Economic, Legal and Social Affairs in Palestine, Transjordan, and Other Parts of the Arab World. Her cartoons conveyed rejection of the Balfour Declaration and the Partition Resolution, and criticism of British political actors who deferred to treacherous Zionist ambitions and the activities of the Zionist movement.

Halaby criticized Zionist indoctrinations and influence over the British Mandatory government. She referred to the parable of Samson and Delilah from the Bible to draw attention to the authority exercised by the Zionist organization over influential figures in the British government. According to her, the relation between British officials and Zionists leaders was marred by imprudence and was pushing the British government, represented by Winston Churchill, into the abyss. Her cartoons warned against the threat of Jewish immigration and argued that Palestine could not absorb large numbers of Jewish immigrants from all over the world, since contrary to Zionist claims Palestine was not vacant. She criticized the British for allowing illegal immigration of Jews and the role of foreign financing of land purchases. She voiced the Palestinian bourgeoisie admonition against the British Mandate for not protecting Palestinian neighborhoods and villages from acts of theft and violence carried out by Zionist groups. She condemned the educational system, which draws on Zionist propaganda, and noted that Zionists take advantage of all sorts of platforms, including education, to deflect attention away from their violence.

Launching an Art Career

After the outbreak of the six-month general strike in Palestine in April 1936, and in response to one of the demands of the national movements to support the Palestinian economy, Halaby registered in the Directory of Arab Trade, Industries, Crafts and Professions in Palestine and Transjordan (1937-1938) as a businesswoman creating postcards of the Palestinian landscape. After the defeat of the Great Arab Revolt 1936-1939, Halaby painted to preserve the land of Palestine as she had known it. She drew cityscapes and scenes of Jerusalem area villages. She conveyed the urban Palestinian heritage and cultural sites that unfold layers of Palestinian civilization. Painting was her means of preserving the landscapes as she knew them before the establishment of colonial settlements that had already started covering the hills encircling Jerusalem.

Halaby painted in watercolors the topography of the vast spaces surrounding Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Jericho. Her works demonstrate utmost proficiency and precision, in addition to simplicity, careful selection of details, and mastery in use of color and light. Her paintings depict natural and urban landscapes of the Palestinian cities and their environs; still-life portraits of fruits and flowers; full-body paintings, and portraitures. She painted the Jerusalem Wall encircling the city with a chrysanthemum peaking from a distance, and a painting of the Garden of the Mount of Olives of Gethsemane, and another of the Holy Sepulchre.

The Nakba and the Naksa

Like other families in Qatamon, including the families of Tawfik Canaan and Khalil al-Sakakini, the Halaby family had to leave their house in 1948 after the quarter had been subjected to a number of violent attacks carried out by Zionist groups. The attacks led to setting on fire a number of houses in the neighborhood. The Halaby family took refuge in Al Musrara, in East Jerusalem, to be dispossessed again to Nur Eddein Street in Wadi al-Joz, where she lived with her sister Asia until her death.

In 1967, the Halaby sisters became known for having saved ten Jordanian soldiers chased by Israeli forces. The soldiers took refuge at their house for several days. They were kept in hiding until the sisters managed to smuggle them out wearing civilian dress. They later burned their army uniforms slowly so not to draw the attention of the Israeli army strolling the streets.

Halaby had exhibited her works in Jerusalem starting in the 1950s. She made use of the exhibition opportunities through the YWCA. She participated in the collective exhibition “Palestinian Woman Art Exhibition” curated and directed by Vera Tamari and Faten Toubassi at the Hakawati National Theatre in 1986. She also used the vitrine front of her sister’s shop in al-Zahra Street in East Jerusalem to showcase her paintings. In 2009, Al Hoash Gallery for Palestinian popular art in Jerusalem exhibited her works as part of Jerusalem: Lexicon of Colors exhibition for Palestinian visual arts pioneers.

Sophie Halaby passed away on 21 May 1997 in East Jerusalem and was buried in the cemetery of the Mount of Olives. Sophie had been a victim of fraud; her lawyer, who she had considered a family friend, seized the Halaby family’s property and possession and carelessly disposed of her artworks. Art collectors who recognized the value of her work attempted to locate and collect as many of her paintings as they could. Palestinian artist and academic Samia Halaby considered the loss of Sophie Halaby’s works a great loss to Palestinian art heritage as it bears witness to the loss of Palestinian property caused by the Occupation.

Sophie Halaby is one of the pioneers of visual arts in Palestine and the Arab world. She had a particularly reserved character. She rarely let friends and relatives enter her studio. She also did not exhibit all of her works. She led a restricted social life, yet she was also known for her acute sense of humor. She was known in her area in Jerusalem as the intellectual who studied in France, and taught her cat how to use a fork and knife. Artists who had known her closely such as Vladimir and Vera Tamari remember her distinguished artistic talent in drawing the landscape between Jerusalem to Jericho at an exceptional speed while traveling in a car. And Jerusalem artist Kamal Boullata recalls checking her sister’s store window display on his way to school, impatiently awaiting new paintings by her.

Sources

Ari, Nisa. “Speaking in a Different Key: The Life and Art of Sophie Halaby. ” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 81 (Spring 2020): 155-63.

Boullata, Kamal. Foreword to Sophie Halaby in Jerusalem: An Artist’s Life, xi-xvi. New York: Syracuse University Press, 2019.

Halaby, Samia. “Sophie Halaby, Palestinian Artist of the Twentieth Century.” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 61 (Winter 2015): 84-100.

Schor, Laura. Sophie Halaby in Jerusalem: An Artist’s Life. New York: Syracuse University Press, 2019.

Related Content

Popular action

Great Palestinian Rebellion, 1936-1939

A Popular Uprising Facing a Ruthless Repression