| Year | Arab | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 1112 | 1112 |

| 1944/45 * | 1330 | 1330 |

| Year | Arab | Jewish | Public | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1944/45 * | 2515 | 2795 | 1796 | 7106 |

| Use | Arab | Jewish | Public | Total | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1555 | 2641 | 258 | 4454 (63%) | ||||||||||

|

960 | 154 | 1538 | 2652 (37%) |

The north and south parts of the village were located in the midst of a plain, on the west side of the coastal highway. The Village Statistics, 1945 considered these parts as two separate entities. Originally, the area had been known as the River of Wadi Iskandaruna; the name was changed to Wadi al-Hawarith after the tribe of Haritha settled around there during the second half of the sixteenth century and the early part of the seventeenth century. The Haritha tribe itself has been traced to the tribe of Bani Sunbus, who, in turn, are said to have descended from Tayyi, and ultimately from al-Qahtaniyya, a Yemeni tribe that split into sub-tribes and moved to the Hijaz, Iraq, Palestine, and Syria in the early days of the Islamic conquest. The people of Wadi al-Hawarith were a clan of Bani Sunbus.

Until 1929 the people of Wadi al-Hawarith worked the village land as tenants. In that year they entered into a protracted battle against the Jewish National Fund (JNF) which had purchased their land from absentee landlords. The JNF, was the World Zionist Organization's body in charge of land purchase and development. Established in 1901 and still active, it is registered today as a tax-exempt corporation in New York. In 1929, the inhabitants of Wadi al-Hawarith began resisting the measures adopted by the JNF to evict them from their land. In that year their numbers were variously estimated at 850 (by the Jewish Agency's Settlement Department), 1000-1,200 (by the British high commissioner) and 1,500 (the count made by the head of the tribe). According to the high commissioner, the tribe cultivated 10,000 to 15,000 dunums and pastured their animals on an additional 10,000 dunums.

During the 1930s, their story became a national symbol for Palestinians dramatizing their fears of a Zionist takeover of the land. The following account is based for the most part on Adler (Cohen) (1988) and to a much lesser extent on Stein (1984:70-79).

The land of Wadi al-Hawarith, which amounted to about 30,000 dunums, was originally owned by the family of Antun Bishara al-Tayyan, who had resided in Jaffa. Al-Tayyan apparently had mortgaged the land during the Ottoman period to a French citizen, Henry Estragin. When al-Tayyan's thirteen heirs decided to sell the land, seemingly to repay their father's debt to Estragin, the representative of the JNF agreed with them in November 1928 to purchase the land at an auction. A court-sponsored auction was held on 20 April 1929. The auction price of the land was 41,000 Palestinian pounds (£P); however, the actual price paid by the JNF to the heirs was close to 136,000 Egyptian pounds, or nearly three times the auction price. Sealing the deal at the court ensured the anonymity of the al-Tayyans, who sought to avoid public criticism, and also enabled the JNF to circumvent the tenants.

When, on 6 September 1930, the court ordered the tenants of Wadi al-Hawarith to leave the land, they refused and resisted the order in several ways. They appealed to the courts several times, but their appeals were turned down; the legal channels were exhausted by December 1932 when the High Court gave its verdict in favor of the JNF and against the tenants. In the meantime, the tenants tried to impede the establishment of a Jewish settlement on the newly acquired land, but by 1931 the settlers had planted 43,000 saplings, which were described in the 1928-35 protocols of the JNF as 'soldiers defending the homeland.' They also appealed to the British Mandate authorities, who made several offers to resettle them elsewhere in the country-offers the tenants did not accept. They took temporary refuge in other villages that offered to host them and worked with the nationalist movement. But finally, in June 1933, those who were in the area in which the JNF had planted trees (by then known as the 'disputed area') were expelled.

After their expulsion (they were given compensation by the JNF for the sorghum and melons that they had already planted), they returned to harvest their crops. The JNF allowed the tenants, whom they referred to as ' these wretches,' to do so. By 1944/45 they had planted 950 dunums in cereals.

The insistence of the people of Wadi al-Hawarith to remain on their land came from their conviction that the land belonged to them by virtue of their having lived on it for 350 years. For them, ownership of the land by absentee landlords was an abstraction that at most signified the landlords' right to a share of the crop. The tenants understood that the loss of their land would mean the dissolution of their tribal structure, which indeed happened soon after the eviction. Some members of the tribe became seasonal laborers, some took government jobs, and some relocated, but a number of them stayed in the vicinity. Adler (Cohen) puts the number of the villagers who remained nearby at 300, but the 1944/45 census suggests that this may be an underestimate. The rest of the villagers moved elsewhere. Those who stayed were able to build twenty-three houses by 1935. In 1944/45 the villagers numbered 1,330 (850 North and 480 South), and cultivated cereals on 950 dunums. By 1937 the Zionist settlers were able to cultivate nearly 22,000 dunums in the area around Wadi al-Hawarith.

After facing a psychological warfare operation designed to induce the residents to leave, Wadi al-Hawarith was attacked by the Haganah. According to Israeli historian Benny Morris, the combined effect of physical and psychological warfare apparently led to the departure of the residents on 15 March. The Haganah operation was conducted in coordination with similar operations in late 1947 and early 1948 that were designed to clear the coastal plain north of Tel Aviv of its Arab inhabitants. This casts doubt on the claim made by the History of the Haganah that the evacuation of the Wadi al-Hawarith area was 'organized by the Arab leadership,' and that it was one of the first cases of civilian depopulation during the war.

The final blow to the village was dealt at the end of April and early May. The Haganah, assisted by local Jewish settlements, destroyed the houses of this and neighboring villages, rendering a return 'all but impossible,' in Morris' words.

Zionists established the settlement of Kefar ha-Ro'e (142199) on village lands in 1934. Kefar Witkin (138198) was built one year earlier, in 1933, but was south of the lands belonging to Wadi al-Hawarith. Ge'uley Teyman (141199) was built on what had been village lands in 1947. Kibbutz Ma'barot (141196), established in 1933, lies close to the southwest of Wadi al-Hawarith South, and Mikhmoret (138201) lies close to the west of Wadi al-Hawarith North, but neither is on village land.

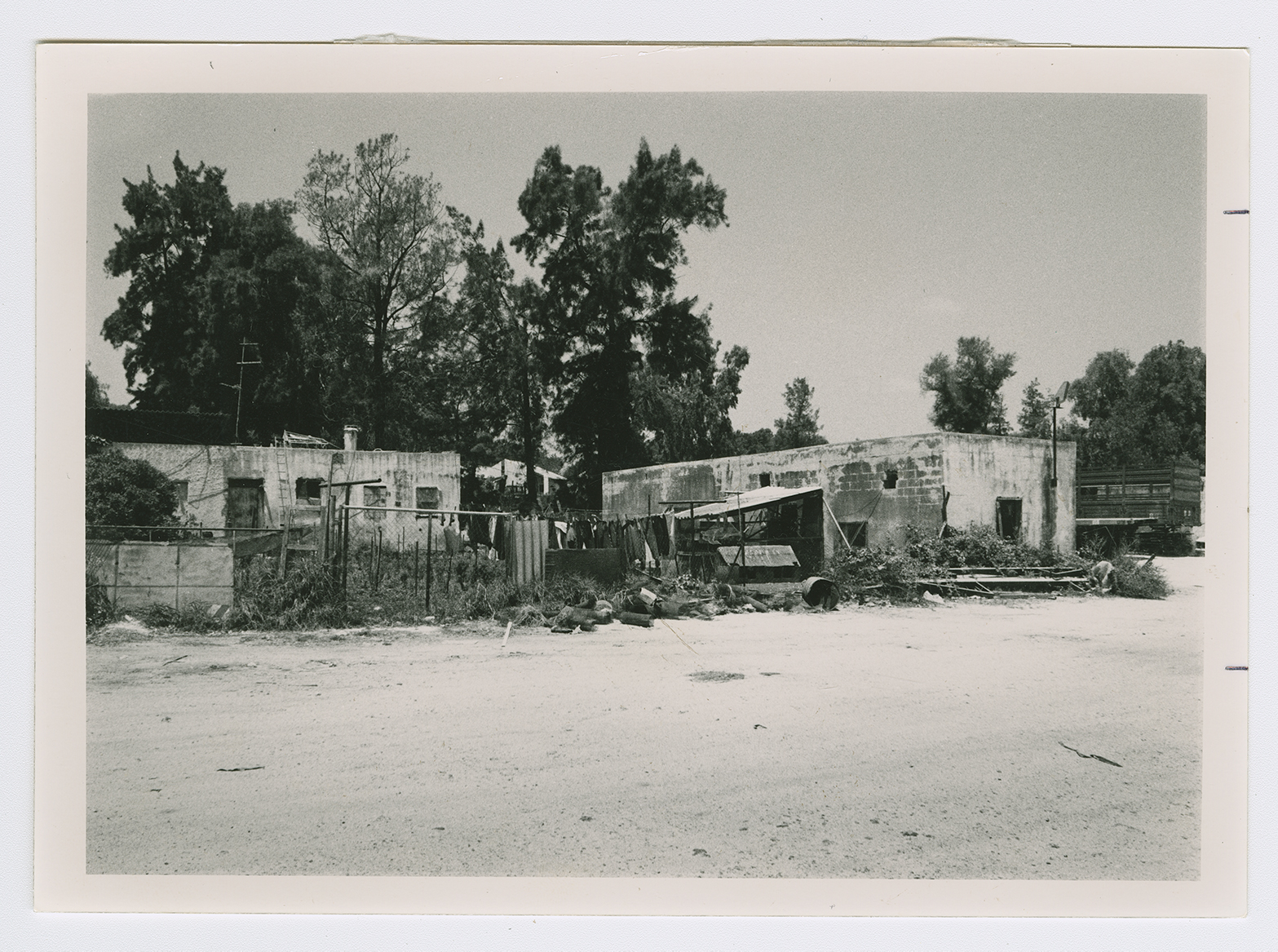

One family (that of Abu 'Isa al-Hajibi) remained in Wadi al-Hawarith North after 1948; its members now have ten houses there. On the southern edge of these houses is the settlement of Ge'uley Teyman. On the site of Wadi al-Hawarith South, four village houses have survived; one of them is occupied by an Israeli family (see photo).