| Year | Arab | Jews | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 1347 | ||

| 1944/45 | 2010 | 210 | 2220 |

| Year | Arab | Jewish | Public | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1944/45 * | 13838 | 3468 | 595 | 17901 |

| Use | Arab | Jewish | Public | Total | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

*includes Gat **includes Gat |

336 | 35 | 581 | 952 (5%) | |||||||||||||||

*includes Gat **includes Gat |

13502 | 3433 | 14 | 16949 (95%) |

The village was situated in an area of rolling hills, where the coastal plain and the foothills of the Hebron mountains merged, and was bordered on the western side by Wadi Fattala. It was on the south side of the highway between al-Faluja, to the northwest and Bayt Jibrin (an important village in the Hebron sub-disctrict), to the east. Its name, Iraq al-Manshiyya, expressed both the geography and history of the village. The first part, Iraq ('small hill' in Arabic), referred to the topography. The second part, al-Manshiyya ('the built one' in Arabic), was added by the inhabitants to distinguish it from a nearby village, also known as Iraq, from which they had moved. In 1596, Iraq al-Manshiyya was a village in the nahiya of Gaza (liwa' of Gaza), with a population of sixty-one. It paid taxes on a number of crops, including wheat and barley, as well as on other types of produce such as goats and beehives.

In the late nineteenth century, the village of Iraq al-Manshiyya was built of adobe bricks and surrounded by arable land. The village had a radial plan, with its smaller streets branching out from the intersection of the two perpendicular main streets. The intersection of these two streets formed its center. Three wells supplied the village with water for domestic use. As the village grew, it expanded toward the highway and northeastward in the direction of Tall al-Shaykh Ahmad al-Urayni. This large mound, some 32 m high, rose to the north of the village, and on its summit was a religious shrine for Shaykh Ahmad al-Urayni.

Iraq al-Manshiyya's Arab population was Muslim. It had an old mosque and a more recent one that was considered one of the most handsome among village mosques; it contained several rooms, a portico, and a courtyard. The village also had an elementary school, founded in 1934, with an enrollment of 201 students in the mid-1940s.

The inhabitants worked primarily in agriculture, growing grain, grapes, and many varieties of trees (such as olive and almond trees). Agriculture was mostly rainfed, despite the availability of groundwater, especially along the line where the plain intersected with the nearby foothills. In 1944/45 a total of 13,449 dunums was allotted to cereals; 53 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards. Goats and sheep supplied the materials (hair and yarn) needed for rug weaving. The villagers dyed their rugs in al-Faluja, where they also went for medical treatment and other services.

The mound next to Iraq al-Manshiyya was for some years erroneously identified with the biblical (Philistine) city of Gath. However, when the site was excavated (1956–1961) no traces of a Philistine presence were found. These excavations (and later work in 1984) determined that a settlement had been established there in the fourth millennium B.C. and had been occupied until the second century B.C. The tell contains the ruins of this settlement. As is the case for many sites in Palestine, its later history continued on a new location below this tell—that is, on the site of Iraq al-Manshiyya.

The Giv'ati Brigade unsuccessfully attempted to occupy the village at the end of July 1948 during the second truce of the war, according to Israeli historian Benny Morris. The New York Times reported on 28 July that Israeli forces were attacking Egyptian communications and vehicle concentrations at Iraq al-Manshiyya. Two days later, a dispatch spoke of 'rather serious engagements between Hatta and Iraq el Manshiya.' Palestinian historian Aref al-Aref writes that the village was the target of 'continuous attacks' during the second truce, notably on 22 August.

A large-scale attempt was made to occupy the village when the second truce ended, at the beginning of Operation Yoav , on 16 October. This time, the Israeli army was beaten back decisively by Egyptian forces, but not before an armored column succeeded in storming the village. An Israeli spokesman quoted in the New York Times said that in forcing its way into Iraq al-Manshiyya, 'the Israeli Army shot up the village, killed a number of Egyptians and destroyed dumps and guns….' The spokesman described the attack as a 'punitive raid' and admitted losing three tanks.

A final assault was executed on 27–28 December by units of the Alexandroni Brigade, which managed to enter the village only to be driven out again by Egyptian reinforcements. At the end of the war, the village was located inside the 'Faluja pocket,' an enclave in which 3,000 Palestinian civilians and one Egyptian Brigade (one of whose officers was Egypt's future president, Gamal Abdel Nasser) were trapped. Morris says that within days of signing the Israel–Egypt armistice agreement, on 24 February 1949, Israel violated its terms by intimidating into flight the 2,000–3,000 villagers of Iraq al-Manshiyya and neighboring al-Faluja. According to the United Nations mediator, civilians in the enclave had been beaten and robbed by Israeli soldiers; cases of attempted rape were reported. Morris reports that the decision to intimidate the population into fleeing their villages was probably taken by the Israeli commander of the southern front, Yigal Allon, probably with the approval of Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion.

A kibbutz named Gat was established in 1941 on lands that traditionally belonged to the village; it took over additional lands in 1949 after the expulsion of the villagers. Six years later, in 1954, Qiryat Gat was established on village lands; Sde Moshe was established in 1956 on village land east of the village site.

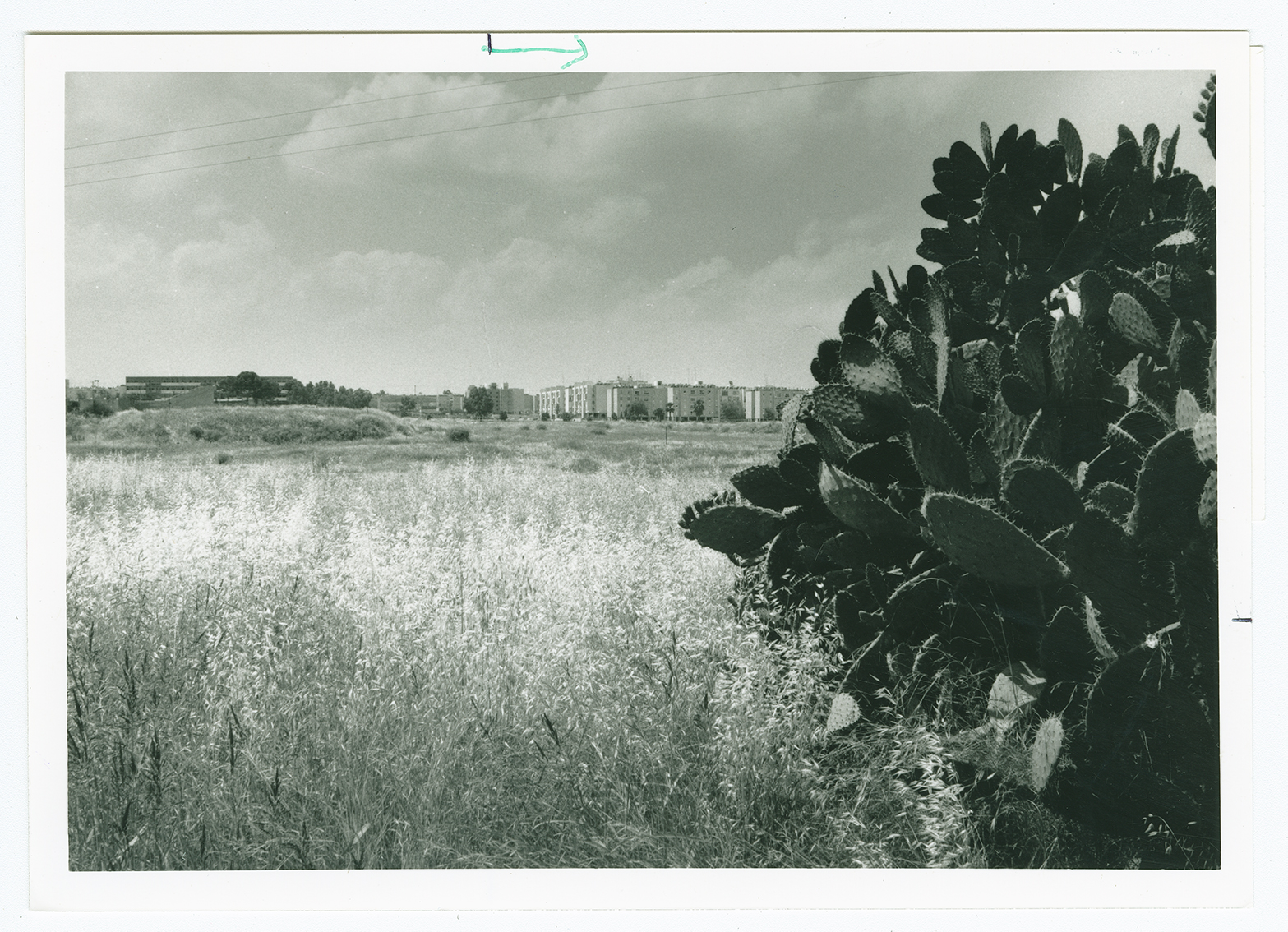

A forest of eucalyptus has been planted on the site, and two signs, each in both Hebrew and English, identify it as the "Margolin Peace Forest." Only traces of the village streets remain, along with scattered cactuses. Part of the surrounding land is cultivated by Israeli farmers.

Related Content

Violence

Operations Yoav and ha-Har in the South Put End to 2nd Truce

1948

15 October 1948 - 4 November 1948

The rubble of destroyed houses, viewed from the center of the site looking northeast. Some Israeli industrial buildings surrounded by a fence are visible in the background. The site is part of an industrial park that includes the Pulgat clothing firm.

Rubble viewed from the center of the site looking west. The railroad track can be seen under the trees on the horizon.

An Israeli settlement on village lands.