| Year | Arab | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 171 | 171 |

| 1944/45 | 290 | 290 |

| Year | Arab | Public | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1944/45 | 1105 | 587 | 1692 |

| Use | Arab | Public | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

587 | 587 (35%) | |||||||

|

1105 | 1105 (65%) |

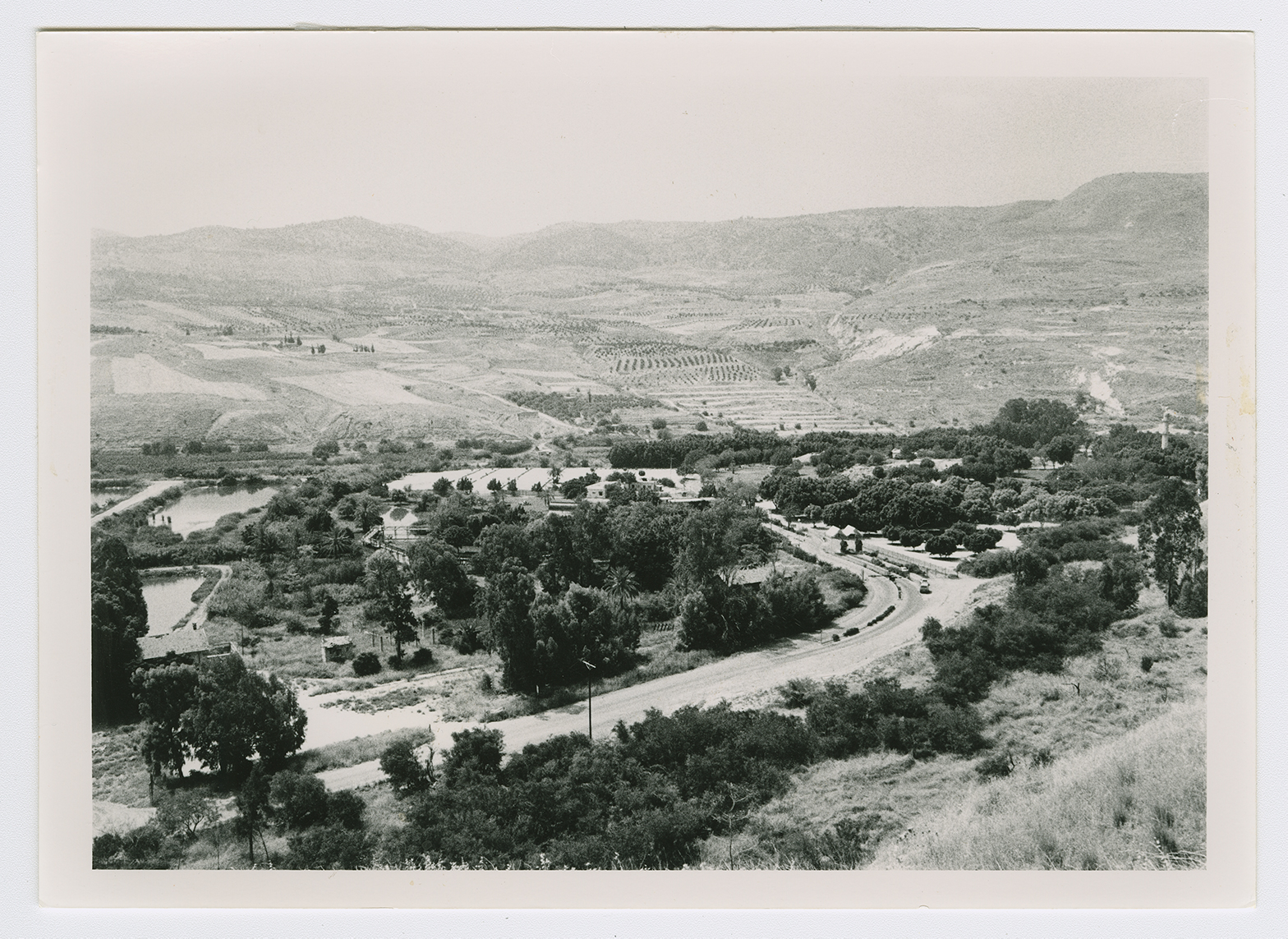

The village was situated on a narrow strip of land in the Yarmuk Valley. Steep slopes rose to the north and south. It was one of the stations on the railway line that linked Haifa to the Hijaz railway through Samakh on the southern tip of Lake Tiberias. The area had attracted settlers since ancient times. Al-Hamma was established on the Hellenistic Ammathous, the Old Testament's Ammath (or Emmath). In the Roman period, the site was called Emmatha and belonged to the sub-disctrict of Gadara (Umm Qays), now located in Jordan. Al-Hamma was renovated in A.D. 663, during the reign of the Ummayyad caliph Mu'awiya, after it had been damaged by an earthquake. It was known for its hot springs, which were thought to have therapeutic qualities because of the high sulfur content of their water. Although the springs attracted many visitors in the days of the Greeks and Romans (as evidenced by modern excavation and by references to the springs in historical works), they were later abandoned and were visited only by Bedouin, who set up seasonal camps at the site. A Lebanese entrepreneur, Sulayman Nasif, was given a concession in 1936 (during the British Mandate) to exploit the springs. Afterwards Palestinians and other Arabs flocked to the area for relaxation and therapy.

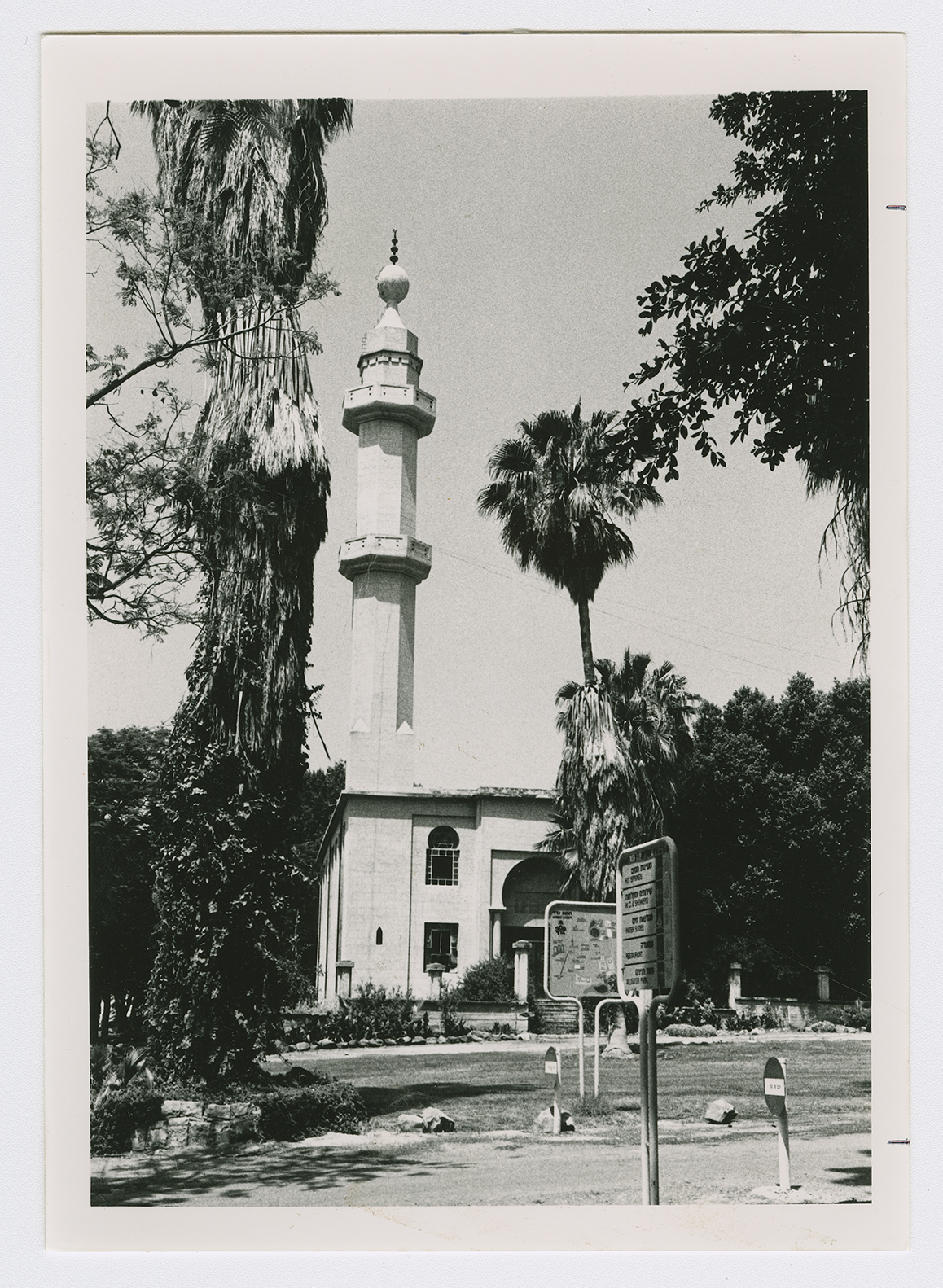

The people of al-Hamma were predominantly Muslim, and the village had a large mosque with marble columns and a fountain in its front courtyard. Agriculture constituted the main source of livelihood for the villagers; a small portion of the village lands was planted with olive trees, and in 1944/45 a total of 1,105 dunums was irrigated or used for orchards. Archaeological remains in al-Hamma included an amphitheater, baths, a synagogue, burial grounds, the shafts and capitals of columns, and a shrine.

Al-Hamma was not captured in combat but was seized well after the fighting had ended. At the end of the war, the village fell within the Demilitarized Zone on the Syrian border, and was protected under the provisions of the Syrian-Israeli armistice agreement (Article V) signed in July 1949. However, as Israeli historian Benny Morris writes, the Israeli authorities nevertheless decided to eject the inhabitants of the cluster of villages covered in the agreement, on grounds that they may have been helping the Syrians, stealing cattle, and trespassing. Over the next seven years (between 1949 and 1956), 'a combination of stick and carrot' was employed in order to drive them out, according to Morris. The methods used were 'police pressure and 'petty persecution,' and economic incentives.' Most of the area residents moved to Syria, but some were relocated to the village of Sha'b in Acre sub-disctrict.

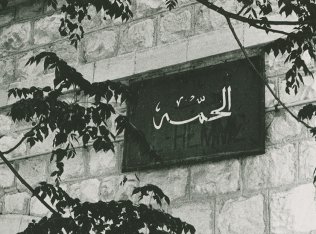

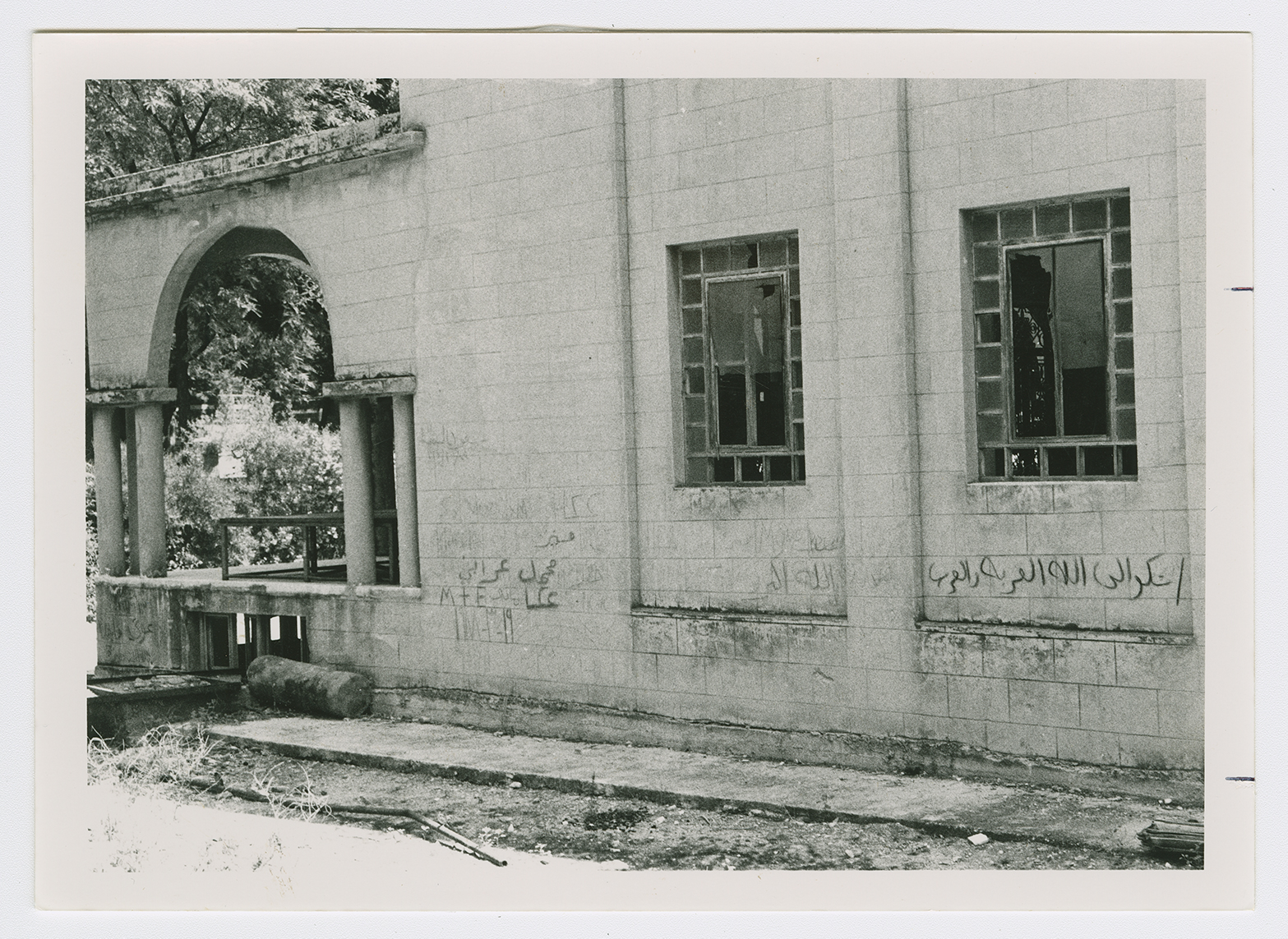

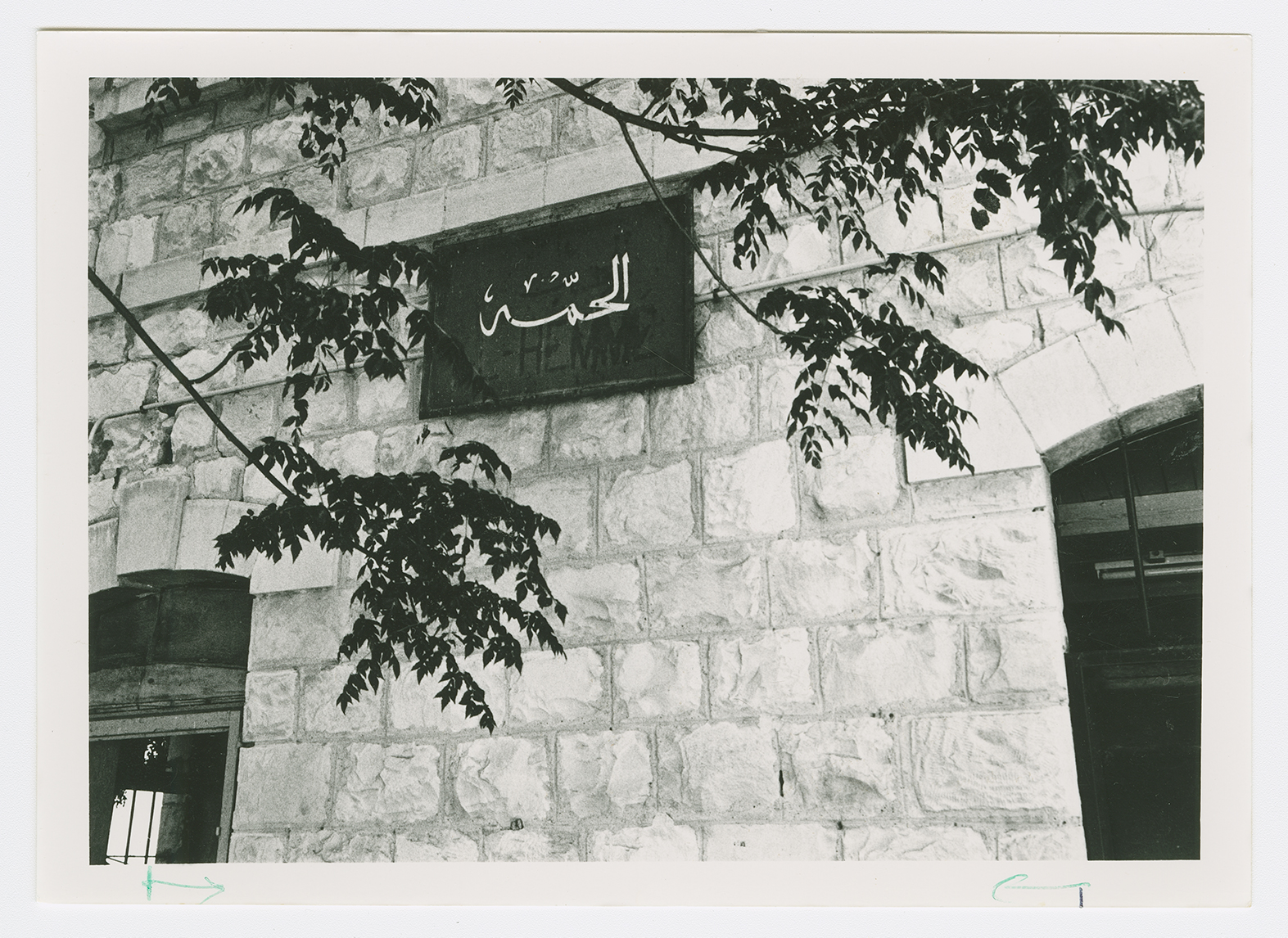

The site has been converted into an Israeli tourist park, with parking facilities, swimming pools, and a small fishing pond. The deserted mosque still stands, and its minaret and marble columns are intact. Building foundations that were unearthed by an archaeological excavation can be seen south of the mosque. Five buildings east of the village site are built of black basalt. The railroad station still exists and the name of the village is inscribed on its entrance. There are three more deserted buildings next to the station, as well as the remains of destroyed houses (see photos).

Graffiti on the western wall of the mosque: "I complain to God about Arabism and the Arabs."

A house on the village site.

The village mosque from the east.

A general view of the village area (middle ground) seen from north to south.

The former railway station with an Arabic sign reading "al-Hama."