During the 19 months of the

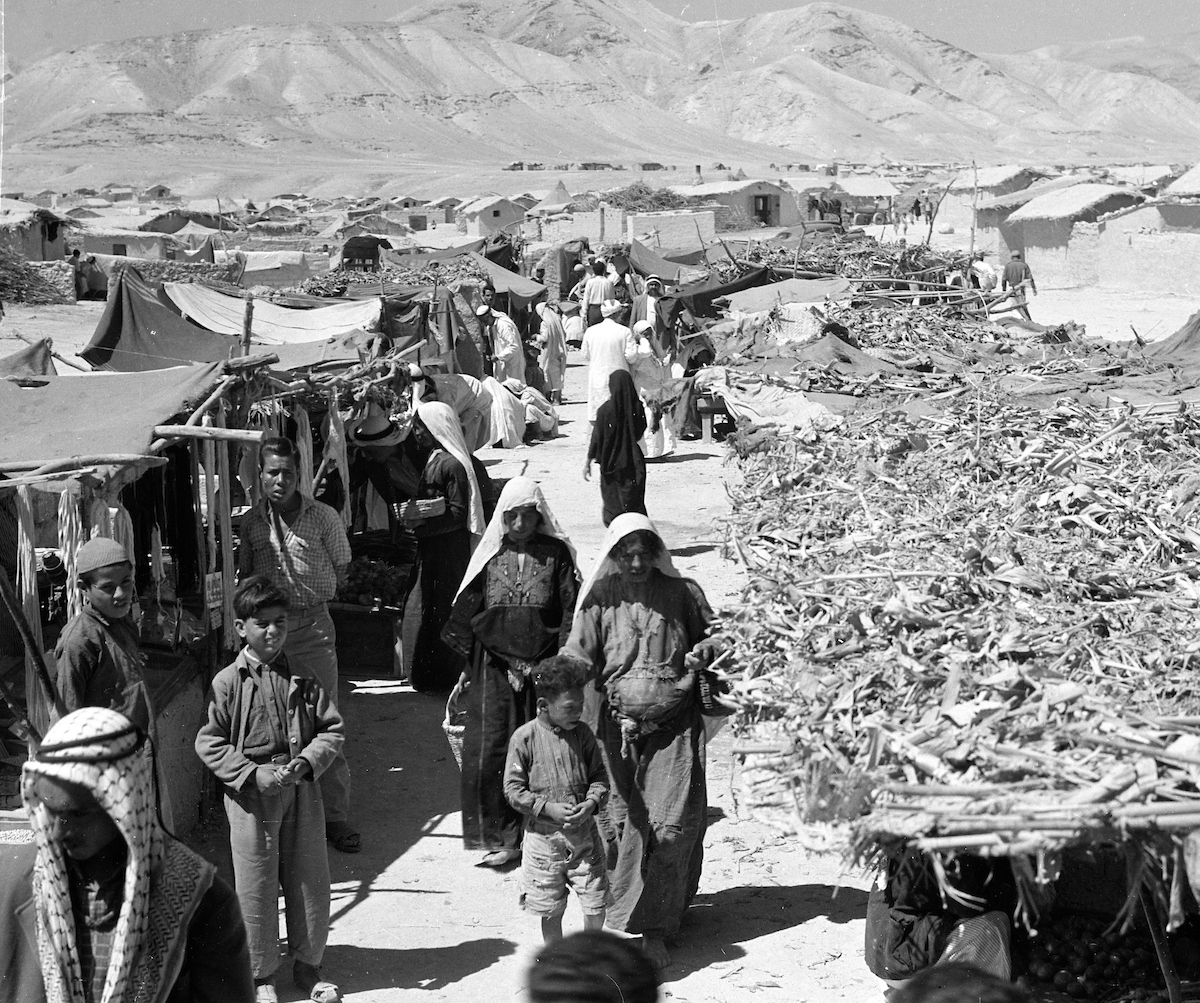

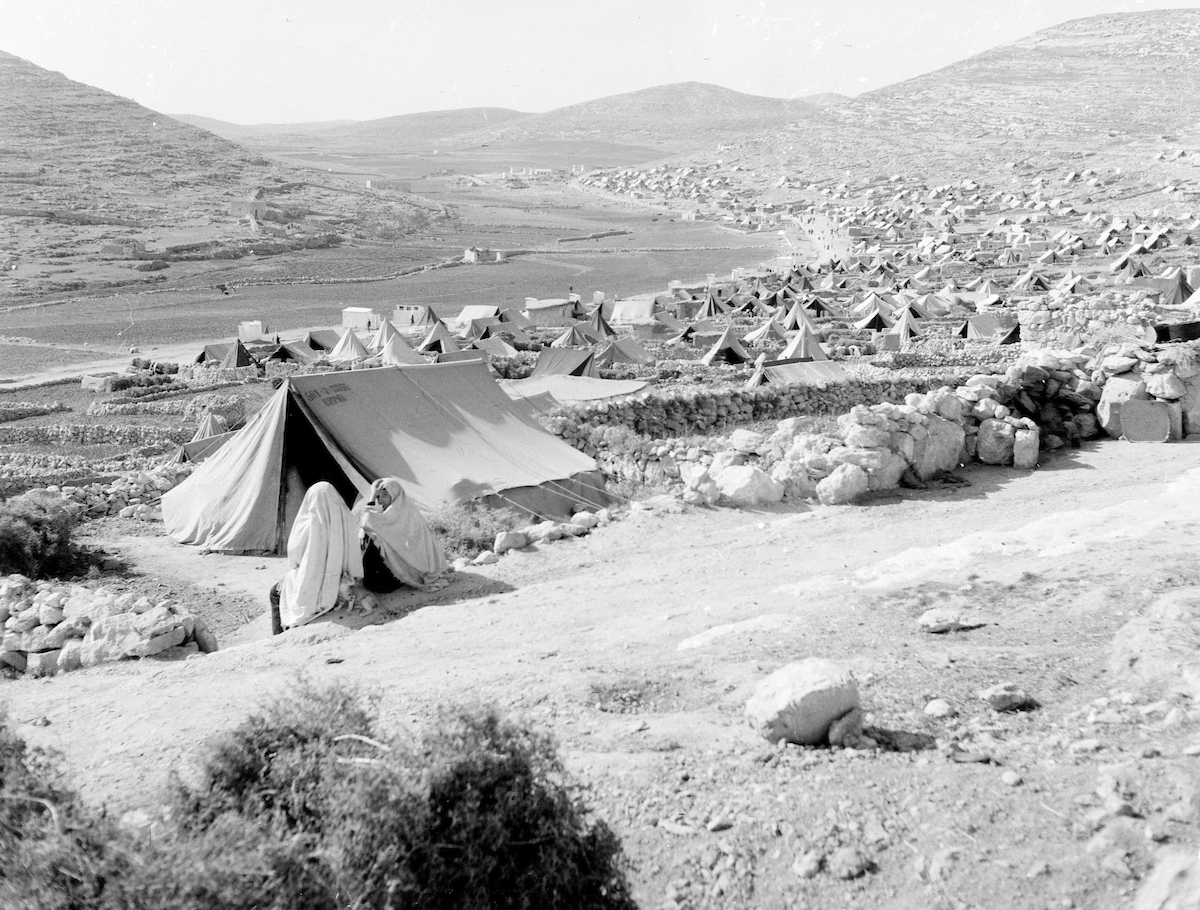

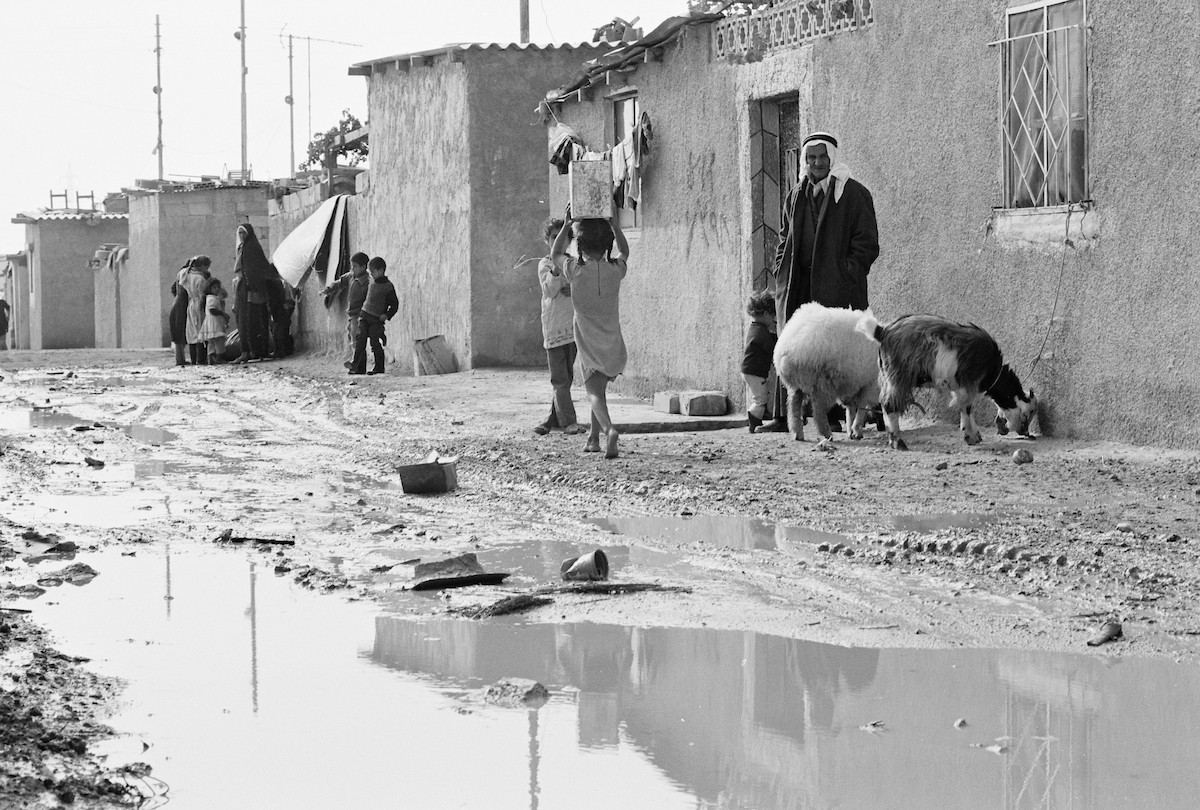

In the early phase, many refugees found shelter in abandoned buildings, old military barracks, schools, mosques, churches, or with friends and relatives. Many waited in tented camps near the borders and later moved to re-unite with family; find work; and access relief, medical care, and education. During the immediate crisis, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) provided tents, food rations, tented schools, and medical assistance. During fall 1948,

About one third of the Palestinian refugees would end up living in refugee camps. Today, more than seventy years later, fifty-nine official refugee camps exist, along with unofficial gatherings. While anthropologists, geographers, and architects have contributed significantly to research on Palestinian refugee camps, this is a blind spot for historians.

The Emergence of Camps

Initially, many tented camps organized by NGOs were situated in isolated spots near borders where refugees gathered. The Jordanian and Lebanese governments transferred refugees to new camps away from the borders. UNRWA maintained that it was important to avoid the establishment of camps where there were few employment opportunities. For UNRWA, large centrally located camps were easier to access, maintain, and administer than small, dispersed camps.

UNRWA reported that refugees were clamoring to enter camps, and that the number of refugees living in camps grew quickly. At the same time, many refugees were “squatting” in

In 1951, UNRWA started constructing huts, which were seen as providing better accommodation than tents and were less expensive to build and maintain because they did not require periodic replacements. UNRWA also encouraged refugees to erect small structures: mud brick in the

While the basic function of the refugee camp is temporary residence, assistance and containment, over time camp inhabitants formed the camps’ functions, including their social, military and political dimensions. At the same time, the temporary refugee camp symbolizes the right of return, but also refugees’ suffering and struggles against permanent integration. The refugee camps have similarities but have also evolved in different ways. Their development depended on a large number of factors, such as different local contexts, geographies, host countries’ policies, political history of activism, and camp organization. Across the region and over a long time span, camps are ever-changing sites of complex and divided politics and identities.

UNRWA’s Shelter Program

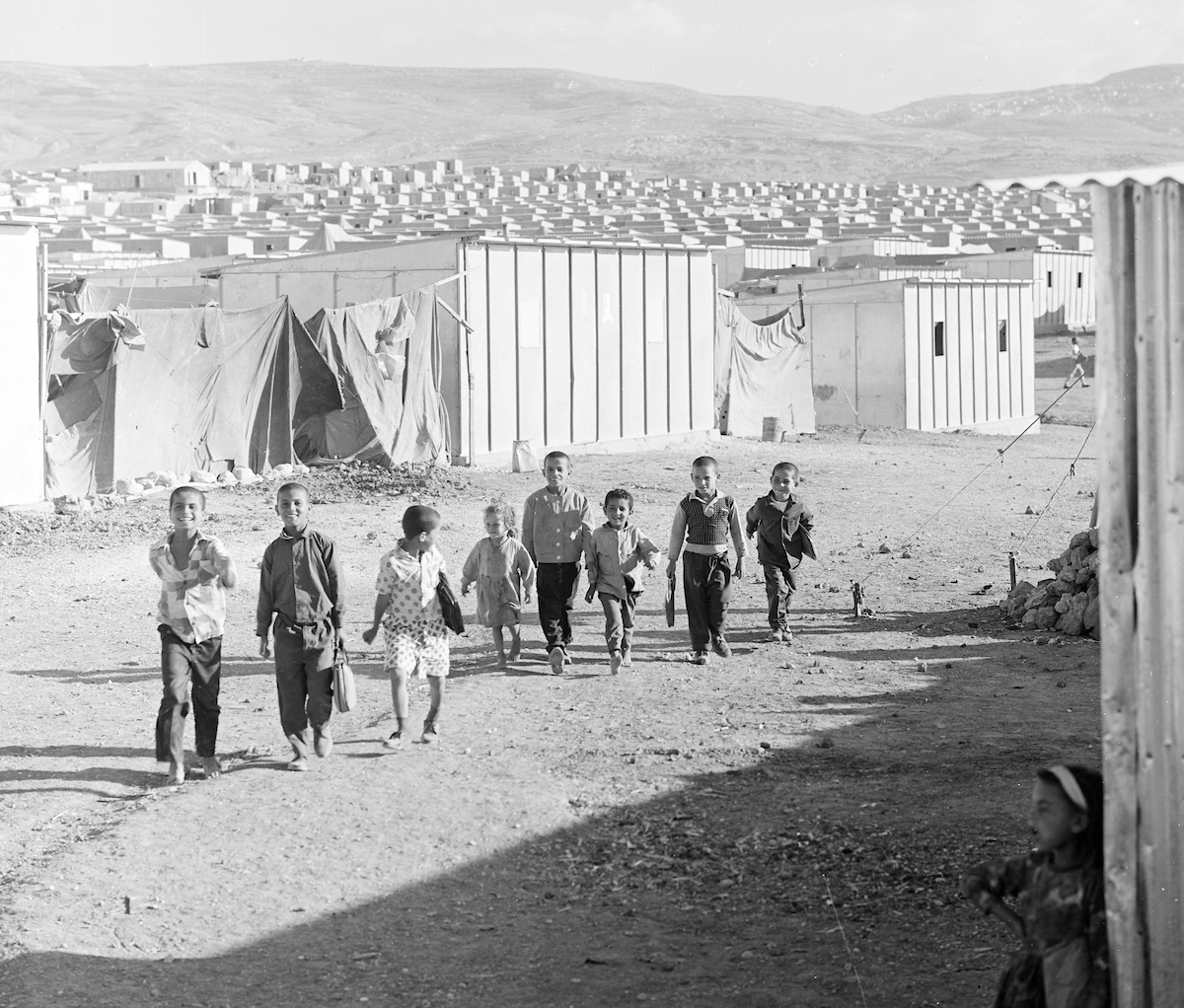

Broadly speaking, three types of camps existed in the 1950s: camps that evolved by refugees’ efforts alone, camps where UNRWA replaced tents with huts or shelters or assisted refugees in this undertaking, and camps built fully by UNRWA. By 1955 UNRWA’s approach moved from ad hoc to a more organized shelter program, the main objective of which was to replace tents with shelters in existing camps. By 1959 most tents were replaced with concrete huts. UNRWA shelters in all locations were based on a generic model: a small hut on a relatively large plot to which the family could add rooms and amenities as they found necessary and could afford. According to UNRWA, camps inhabitants generally built a kitchen, latrine, and additional living room as soon as they could, followed by a wall to enclose the plot.

The second objective of the shelter program was to provide grants of materials or money to encourage camp inhabitants to construct their own shelters, often presented as self-help. The practices, however, varied greatly. On the West Bank,

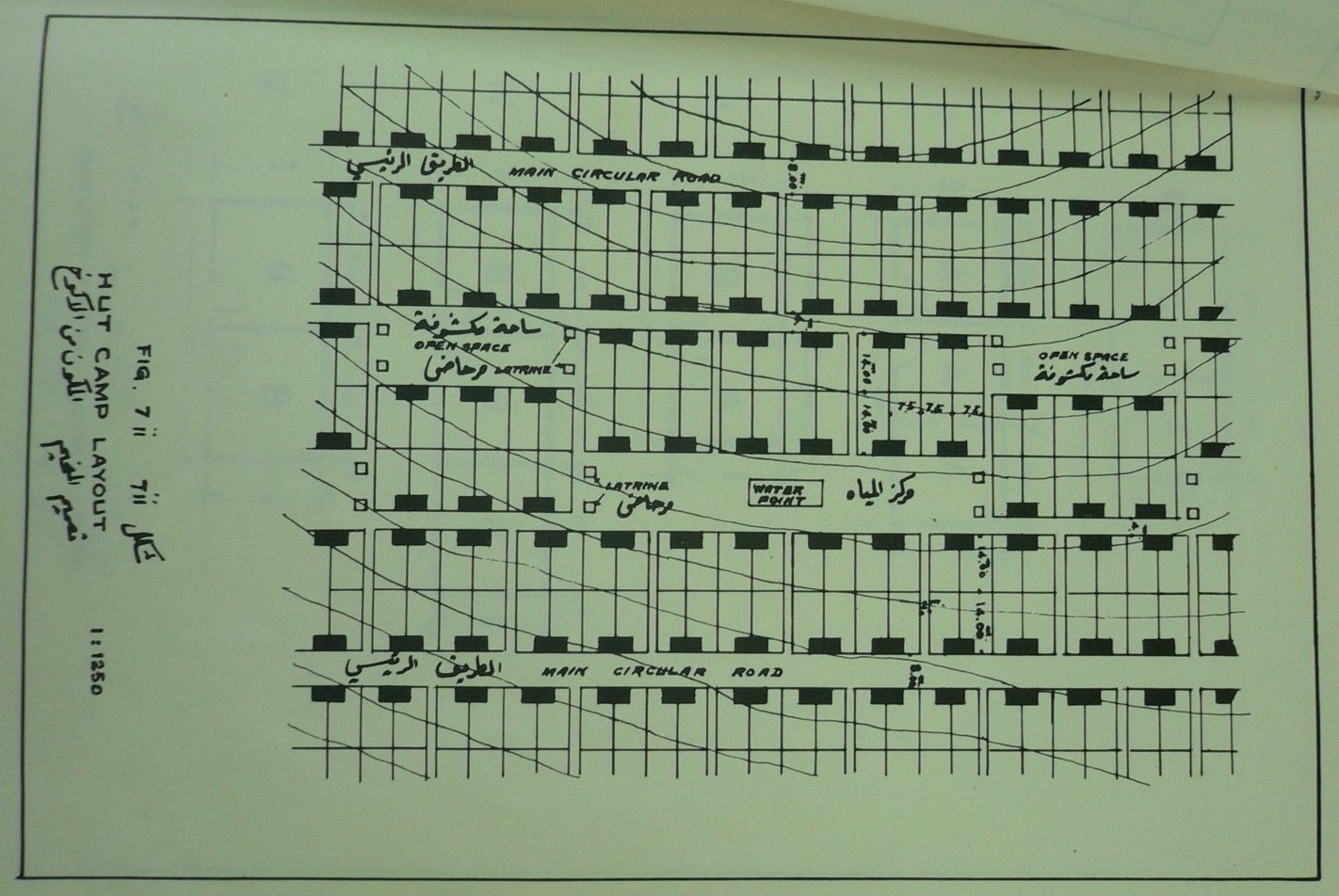

The third objective of the shelter program was to build new camps. One central aim of camps was to bring order, low population density, and improved hygiene to the site. The layout plan (reproduced below) included twin shelters (black squares) with adjoining plots (white squares). There were specific zones for shelters, water sources, latrines, and open spaces and for installations like schools, clinics, and centers, connected by a system of circular roads.

Despite the disciplinary powers of both UNRWA and the host state, the refugees’ own agencies imprinted their own meaning on the space and meaning of the camps. In some camp quarters, refugees reconstructed the pattern of organization in their lost village in Palestine. Settling in such microclusters helped establish belonging, familiarity, and security. Camps symbolized loss and defeat but became a powerful field to organize and express national identity and sentiment.

UNRWA established camp regulations, and one aim was to regulate refugees’ building. In this undertaking, it relied on host country enforcement. Lebanon placed the most restrictions on refugee construction and refugees, but the degree of host country involvement varied. By the 1960s, UNRWA reported that camps were already overcrowded and in need of repair and maintenance. Shelters and camps had been built at low standards, and refugees’ needs were higher than could be met by UNRWA, which was strained by limited funds and refugee and host country attitudes, both resisting integration.

Six New Refugee Camps in Jordan after 1967

The June 1967 War marked the onset of the Israeli occupation, and now both registered Palestinian refugees and West Bank and Gaza residents fled or were expelled to Jordan and Syria. Many sought shelter with relatives and friends, in existing refugee camps, and under trees and in mosques, while others lived in government and UNRWA schools. In an intense three-year process, six new official camps were established in Jordan, and one in Syria. It became increasingly clear that shelter and camp construction did not take place in isolation from politics and ideology.

In Jordan the situation was chaotic. Refugees kept arriving from the West Bank and Gaza, many moved between as many as seventeen camps, and the location of camps also changed. By late 1967, many camps were moved down to the Jordan Valley, possibly as the government attempted to pressure Israel to accept the return of some refugees. From the Israeli perspective the presence of refugee camps near the front line was a looming threat. UNRWA and the government therefore planned new locations with the view to avoid the militarization of the camps, but their plans were quickly interrupted. On 15 February 1968, the Israeli army attacked

By the summer of 1970, UNWRA announced that no refugees remained in tents. But shelter construction was now a hypersensitive issue. UNRWA had to adjust to refugees’ demands and set up shelters explicitly defined as temporary. The

Camps as Battlegrounds

No new camps have been constructed since 1967, but many have been destroyed and rebuilt, and some have been completely erased. Camps have been sites of resistance, militarization, and human rights violations, as host countries have considered them security threats. The Jordanian army violently targeted camps during clashes between the army and Palestinian militants in September 1970. During the Lebanese Civil War

, Lebanese right-wing militias destroyed

In Gaza, Israel has caused extensive destruction in camps, starting in the early 1970s with the large-scale road widening-and resettlement schemes. In

More recently, UNRWA has rebuilt entire camps destroyed by military assaults. In 2002, during the

Complex Sites, on the Margins

By 1970, a new generation was born in the camps and more space was urgently needed. In many camps, a refugee construction boom started, sometimes in violation of UNRWA building regulations; over time, refugees began to buy, sell, swap, and rent shelters, acts that represent a struggle of a propertyless population to live “normally” despite the constraints. Some camps are among the most densely populated places in the world. Camps are not physically isolated from their surroundings, but unemployment and poverty rates are often high. While the Lebanese state policies have consistently discriminated Palestinian refugees, host countries’ practices have varied.

In the 2000s, UNRWA launched a new program for camp improvement, emphasizing refugee participation and the decoupling of demands for improved living conditions from the demand for internationally recognized rights. In Syria, the case of upgrading parts of the old

The long Palestinian exile is one of multiple displacements. Palestinian refugees fleeing Syria after 2011 have streamed to existing camps or moved to cities. However, the camp is not an exclusively Palestinian space. Several camps in Lebanon also host Lebanese poor, Syrian refugees, and foreign workers, turning them into more complex sites of urban marginalisation. The Palestinian refugee camps symbolize both the need to implement the right of return and the protracted injustice of exile.

Berg, Kjersti G. “The Unending Temporary. United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) and the Politics of Humanitarian Assistance to Palestinian Refugee Camps 1950–2012.” Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Bergen, 2015.

Berg, Kjersti G. “From Chaos to Order and Back: The Construction of UNRWA Shelters and Camps, 1950–1970.” In Sari Hanafi, Leila Hilal, and Lex Takkenberg, ed., UNRWA and Palestinian Refugees: From Relief and Works to Human Development. London: Routledge, 2014.

Berg Kjersti G., Knarvik, Olaf, Vik, Marie and Mezna Qato. More Than The Humanitarian Gaze: Jørgen Grinde’s photography from the Middle East in the 1950s, University of Bergen, https://marcus.uib.no/exhibition/mer-enn-det-humanitare-blikket

Bulle, Sylvaine. “We Only Want to Live: From Israeli Domination towards Palestinian Decency in Shu‘fat and Other Confined Jerusalem Neighborhoods.” Jerusalem Quarterly 38 (2009): 24–34.

Destremau, Blandine. “L’espace du camp et la reproduction du provisoire: Les camps de réfugiés palestiniens de Wihdat et de Jabal Hussein à Amman.” In Riccardo Bocco and Mohammad-Reza Djalili, ed., Moyen-Orient: Migrations, démocratisations, médiations, 83–98. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1994.

Doraï, Mohamed Kamel. “Palestinian Refugee Camps in Lebanon: Migration, Mobility and the Urbanization Process.” In Are J. Knudsen and Sari Hanafi, ed., Palestinian Refugees: Identity, Space and Place in the Levant, 67–80. London: Routledge, 2011.

Gabiam, Nell. The Politics of Suffering. Syria’s Palestinian Refugee Camps. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016.

Al Husseini, Jalal. “The Evolution of the Palestinian Refugee Camps in Jordan: Between Logics of Exclusion and Integration.” In Myriam Ababsa and Rami Daher, ed., Cities, Urban Practices and Nation Building in Jordan, 181–204. Beirut: Presses de l'Ifpo, 2011.

Khalidi, Muhammad Ali, ed. Manifestations of Identity: The Lived Reality of Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon. Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies, 2010.

Misselwitz, Philipp, and Sari Hanafi. “Testing a New Paradigm: UNRWA’s Camp Improvement Programme.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 28, no. 2–3 (2009): 360–88.

Peteet, Julie. Landscape of Hope and Despair: Palestinian Refugee Camps. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

Plascov, Avi. The Palestinian Refugees in Jordan 1948–1957. London: Cass, 1981.

Sayigh, Rosemary. “A House Is not a Home: Permanent Impermanence of Habitat for Palestinian Expellees in Lebanon.” Holy Land Studies 4, no.1 (2005): 17–39.

Tabar, Linda. “The ‘Urban Redesign’ of Jenin Refugee Camp: Humanitarian Intervention and Rational Violence.” Journal of Palestine Studies 41, no.2 (2012): 44–61.

Related Content

Diplomatic Institutional

UNGA 194 (III): Establishment of a Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP)

1948

11 December 1948