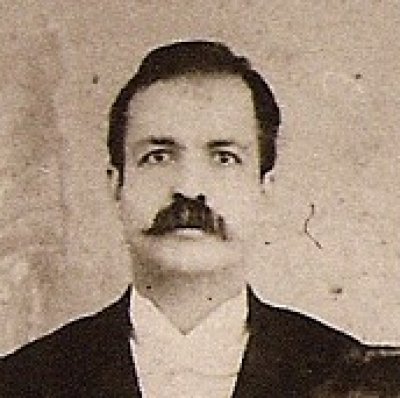

Jurji Habib Hanania

جورجي حبيب حنانيا

Jurji Habib Hanania was born in 1864 in Jerusalem into a Greek Orthodox family that traced its roots back several generations in the city. The family chose to use “Habib Hanania” as its surname—Habib being the given name of an ancestor—to distinguish its members from the rest of the families with the surname Hanania in Jerusalem and across the Levant.

His father Issa, considered one of the Jerusalem’s notables, was the only sitting Christian judge on the Jerusalem Court of Appeals, which was the higher court in the city; his mother, Katingo, was a woman of Greek origin from Istanbul and the daughter of a high-ranking official in the Ottoman administration.

He had a younger brother named Yaqub, who studied at the Greek Orthodox Divinity School in Jerusalem and was fluent in several languages. Upon completing his studies, Yaqub traveled to Russia, where he was hired to tutor the tsar’s daughter in Hebrew, and died there during World War I. His sister, Irene, was married to a man from the Zakaria family; she too died during World War I.

Jurji Habib Hanania was married to Anisa Faraj. They had four children—two daughters named Katherine and Futini, and two sons named Issa and Damian—and a granddaughter named Mary.

Hanania received his primary and secondary education at the Bishop Gobat's School (Zion College) in Jerusalem. Several major figures of Palestine’s intellectual and cultural history graduated from this school, such as Khalil al-Sakakini and Ibrahim Tuqan, where, as pupils, they were exposed to modern European ideas of their time. In addition to his formal education, Hanania continued to self-educate, reading all the books he could get his hands on, and successfully achieved fluency in many languages in addition to his native Arabic: Greek, Turkish, Russian, English, French, German, and some Hebrew. He is said to have been a pious young man who regularly attended church every Sunday and sang in the church choir in both Arabic and Greek. Music was also an important part of his life, and he loved to play the mandolin.

Hanania began his professional career in the field of printing. He established a printing press in Jerusalem in 1894. He then aspired to publish a newspaper in Arabic, so in 1899, he requested permission from the Ottoman authorities to do so, but it was only granted in the summer of 1908 after the restoration of the Ottoman constitution. He launched the first issue of his newspaper, called al-Quds, on 18 September of that year. The newspaper printed three dates on each issue: the Julian solar calendar date (used throughout the Ottoman empire and Russia), the Gregorian date, and the Islamic hijri date.

Al-Quds newspaper was the first private newspaper to be published in the Jerusalem district after the restoration of the Ottoman constitution. Its front page masthead had the slogan “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,” and it identified itself as “a scientific, literary, and informative gazette consisting of four pages, published every Tuesday and Friday. It appears from the information given in the newspaper about subscription rates that it was distributed not only within the Jerusalem region, but also throughout the Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and in North and South America.

In his editorial in the first issue of al-Quds, Hanania tells his readers the story of how he started its publication. He mentions how, in 1894, he established a printing press in Jerusalem, whose printing presses until then were all owned by religious institutions, with the intended goal to plant “the seeds of brotherhood,” treat everyone equally and serve the nation “rather than one particular group in preference to another.” He also mentions that since its establishment and until July 1908, his printing press had published 281 books, “of which 83 were Arabic-language books,” and that since the beginning of 1899, he had been seeking permission from the local government in Jerusalem to publish a newspaper in Arabic, but that his request was only granted until after “despotism was lifted” by the restoration of the constitution in July 1908.

Hanania wrote the al-Quds’s editorials and a large number of its articles. He was assisted by a full-time reporter, Iskandar Sweida, and correspondents Yusuf al-Qarra in Nablus and Khalil al-Mufti in Majdal Asqalan, among others. To fill the newspaper’s pages, he also relied on articles written by prominent writers of the day, such as Isaaf al-Nashashibi, Shaykh Ali Al-Rimawi, Jirjis al-Khoury, Antoun Shukri Laurence, Tawfiq Zaibaq, and Iskandar al-Khoury al-Beitjali.

The inaugural issue of the newspaper states that it was “a purely Ottoman publication that champions nothing but the truth and aims only to serve the country with the utmost sincerity. It will track all signs of despotism, search out all weaknesses, look for local faults, and will limit its subject matter to what improves the country’s image, God willing.”

Hanania had a deep belief in the benefit of the written word to society and in the enlightened role that the press, whose fundamental principle was the freedom of expression, could play in mobilizing public opinion in the country and contributing to creating the right environment for social advancement, particularly after the restoration of the constitution and the abolition of press censorship and restrictions on freedom of expression in the Ottoman Empire.

Hanania believed that there are three principal means for the achievement of progress or modernity: establishing modern-style national schools on a widespread basis, publishing newspapers, and establishing associations. He stressed that interpersonal relationships in modern society are based on the bond of shared national identity, as well as on the rejection of any fanaticism based on race or national affiliation. The prevailing form of government in this society should be the constitutional parliamentary system, whose basis is rule by the people, the equality of all individuals in their rights and duties, and the justness of rulers, who are aware that they “are servants of the nation.”

Hanania joined the Jerusalem branch of the Committee for Union and Progress. He was one of its more prominent members and known as one of the supporters of the preservation of “the Ottoman Commonwealth” (al-Jamiʿa al-Uthmaniyya). He championed the freedom of religious belief, as is evident in the articles printed in al-Quds. He believed that religion and reason were not at odds with one another and criticized religious discrimination. However, regarding the question of what was then known as the Arab Orthodox nahda, or renaissance (i.e. the Arabization of the Orthodox Church in the Jerusalem region, which was controlled by the Greek Patriarch and clerics), he took a more cautious position that was in opposition to the position taken by well-known personalities such as Khalil al-Sakakini and Isa al-Isa, who advocated for the Arabization of the church. He also stressed the necessity of educating women and creating amenable conditions for them to be able to work. He considered “the education of women to be imperative over that of men, because it is women who can be depended upon,” and in his view, “in this day and age, the equality of the fairer sex with men should no longer be seen as unfamiliar, nor is it something odd, but rather it is noble, beneficial, nay it is a must.”

In September 1913, as al-Quds entered its sixth year of publication, Hanania expressed disappointment in the response of the Jerusalem district’s readership to his newspaper and to newspapers in general. He writes: “It is no secret that our newspaper has had fewer issues in its fifth year than it did in the preceding four years. We have been forced to reduce its frequency to once a week for many reasons, the most significant of which is the failure of a large number of our subscribers to pay their dues. And anyone who has tried to work in the newspaper business in our country knows that it is not a profitable trade, because we tend to have this bad habit where one copy of any issue is read by nearly fifty people!”

In 1914, Hanania put together an ambitious plan to further expand his newspaper. He decided to buy a larger, more modern printing press. He took out an insurance policy on it, and bought reams of various types of paper to meet its projected needs. He also mortgaged the machinery of the old printing press against a loan to cover the costs that would be incurred for the new press. However, the political atmosphere at the time was tense, and business slowed down as the drumbeats of the impending war grew ever louder. He was unable to pay the installments of the loan he had taken from the German Bank of Palestine’s branch in Jerusalem and in due course had to declare bankruptcy. The official Ottoman gazette carried an announcement by the German Bank to the effect that the machinery of the printing press owned by “Jurji I. Habib Hanania” would be put up for sale by public auction, because the owner had defaulted on his payments on the loan. The last issue of al-Quds, bearing the number 391, appeared on 16 May 1914 (Julian), 29 May 1914 (Gregorian), corresponding to 5 Rajab 1332 (hijri).

After he declared bankruptcy, Hanania decided to leave Jerusalem. He went to Alexandria, Egypt, to seek help from his Egyptian friends. There, the Greek Orthodox Patriarch (who was a personal friend) provided him with all the support he needed and also introduced him to writers and journalists in the city. At the same time, however, it became impossible for him to keep in touch with his wife Anisse, because all lines of communication were cut between the residents of the Jerusalem district, who were subject to Ottoman rule, and those living in Egypt, which was under British rule.

Hanania settled in Alexandria and began to participate in the city’s cultural life. He continued to pursue his career in publishing and issued an annual calendar with the title “The Jerusalem Effect for the Sons of the Greek Orthodox Church.” He also began to research the history of the Orthodox Church, and he worked with someone called Father Hazboun to compile a dictionary.

The end of World War I was welcome news for Hanania. He was overjoyed when Palestine was declared free from Ottoman rule by the British authorities, yet he did not return immediately to Jerusalem. Possibly he wished to avoid having to face a community that would focus its gaze on his failures, after it had looked upon him as a leader at one time.

Hanania died of a heart attack at his home in Alexandria in 1920, at the age of fifty-six, and was buried in one of the city’s cemeteries.

Jurji Habib Hanania was a man of letters, a journalist, and the founding publisher of al-Quds newspaper. He was an enlightened pioneer of modernity in the Jerusalem region and a trailblazer in the ways and means of achieving it. He is remembered as an extremely strong-willed person, but also as being good-natured and having a keen sense of humor. He paid particular attention to his appearance and took care to always be seen well-dressed and well-groomed.

Sources

Abdul Hadi, Mahdi, ed. Palestinian Personalities: A Biographic Dictionary. 2nd ed., rev. and updated. Jerusalem: Passia Publication, 2006.

Hanania, Mary. “Jurji Habib Hanania: History of the Earliest Press in Palestine, 1908-1914.” Jerusalem Quaterly 32 (2007): 51-69.

"الحمد لله"، "جريدة القدس"، العدد الأول، السنة الأولى، الجمعة في 5 أيلول شرقي، 18 غربي، سنة 1908، ص 1-2.

"خطة هذه الجريدة"، "جريدة القدس"، العدد الأول، السنة الأولى، الجمعة في 5 أيلول شرقي، 18 غربي، سنة 1908، ص 2.

"دخول جريدة القدس في سنتها السادسة"، "جريدة القدس"، العدد 364، السنة السادسة، الثلاثاء في 17 و 30 أيلول سنة 1913، ص 1-2.

سليمان، محمد. "تاريخ الصحافة الفلسطينية 1876-"1918. نيقوسيا: الاتحاد العام للكتاب والصحافيين الفلسطينيين، 1987.

الشريف، ماهر. "جريدة القدس وبواكير الحداثة في لواء أو متصرفية القدس ( 1908-1914)". بيروت: مؤسسة الدراسات الفلسطينية، 2024.

مناع، عادل. "أعلام فلسطين في أواخر العهد العثماني (1800-1918)". بيروت: مؤسسة الدراسات الفلسطينية، طبعة ثانية، 1995.