| Year | Arab | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 470 | 470 |

| 1931 * | 847 | 847 |

| 1944/45 | 690 | 690 |

| 1944/45 ** | 1240 | 1240 |

| Year | Arab | Public | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1944/45 * | 11771 | 15 | 11786 |

| Use | Arab | Public | Total | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

*includes Shaykh Dannun, Shaykh Dawud **includes Shaykh Dannun, Shaykh Dawud |

3767 | 15 | 3782 (32%) | ||||||||||||

*includes Shaykh Dannun, Shaykh Dawud **includes Shaykh Dannun, Shaykh Dawud |

8004 | 8004 (70%) |

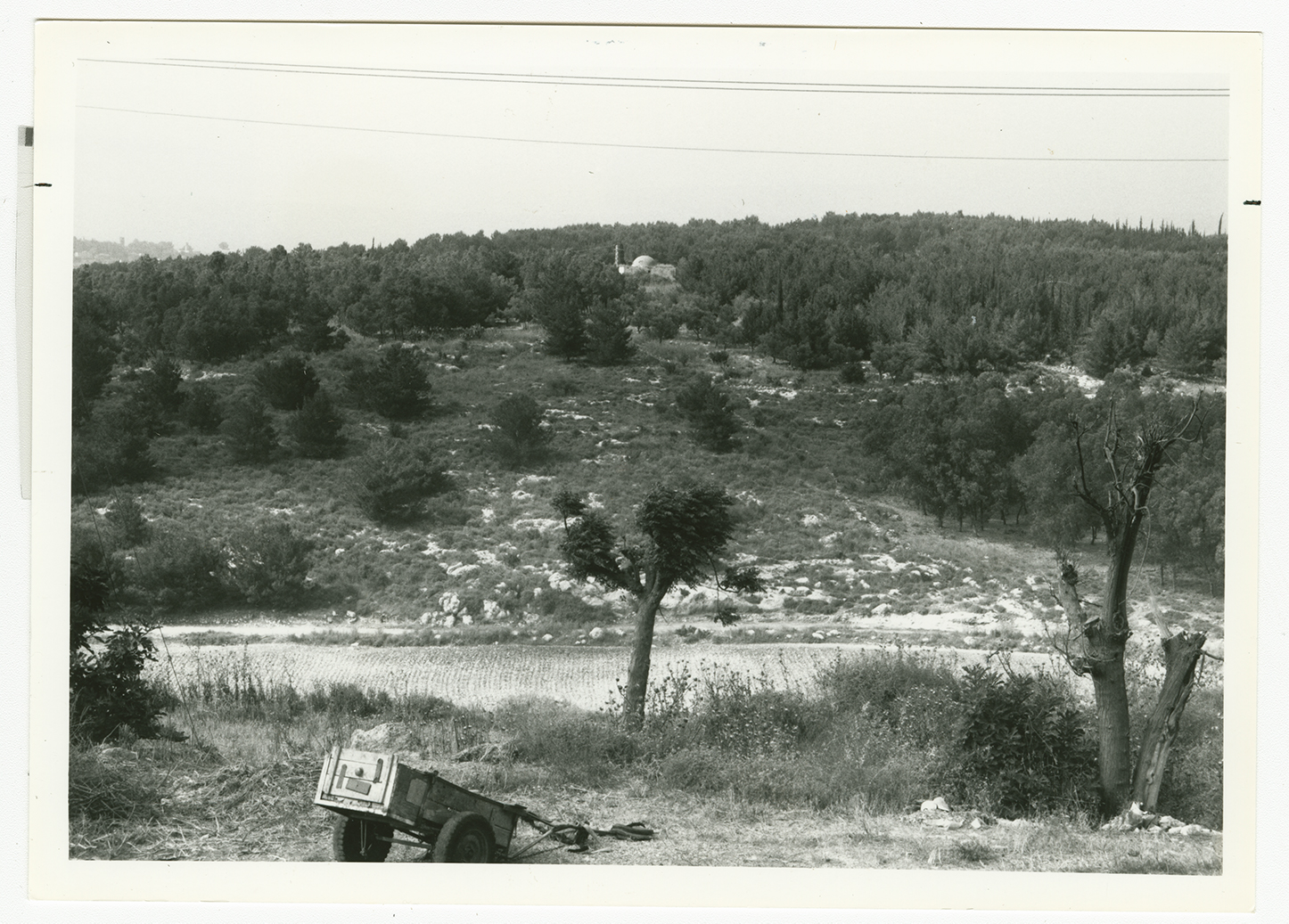

The village stood on a rocky hill that jutted up from the plain of Acre. It was in the foothills of the western Galilee mountains and lay just south of a highway that connected Tarshiha, the Zionist settlement of Nahariyya, and Acre. Judging from the many caves that were used as burial places, the area probably had been a large Canaanite town. In the late nineteenth century, the village of al-Ghabisiyya was built of stone on the ridge of a hill. It was inhabited by about 150 residents and was surrounded by olive trees, fig trees, pomegranate trees, and gardens.

The three villages of al-Ghabisiyya, Shaykh Dannun, and Shaykh Dawud were very close to one another; Shaykh Dannun and Shaykh Dawud actually overlapped at points, but al-Ghabisiyya was about 500 m away from them. The entire population of these villages was Muslim. Al-Ghabisiyya had a school, built by the Ottomans in 1886. The village houses were built of reinforced concrete or, in some cases, stones held together with a mortar of mud or cement. The economy of the village was based on livestock-raising and agriculture; grain and vegetables were the chief crops. The villagers also grew olives, which they processed on two animal-drawn presses, one in al-Ghabisiyya and one in Shaykh Dawud. In 1944/45 a total of 6,633 dunums of the lands of the three villages was allocated to cereals; 1,371 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards. In the same year 300 dunums in al-Ghabisiyya were devoted to olive trees.

Al-Ghabisiyya fell at the end of Operation Ben-Ami, the Haganah's invasion of the northwest corner of Palestine. The attack was waged from two directions, the north and southeast, according to the testimony of some of the villagers interviewed by Palestinian researcher Nafez Nazzal. The occupying forces captured a house in the southernmost corner of the village and proceeded to shell the village from the house, killing and injuring many of the villagers while they were fleeing. Others had been evacuated earlier, due to the fall of Acre. The village militia decided not to confront the Zionist forces, because " we were too few [around twenty] and very poorly armed" as some villagers later recalled. Most of those who were driven out remained in other villages in Galilee until the whole region fell at the end of October 1948; after that, they were displaced to Lebanon. But according to Israeli sources cited by Morris, some inhabitants remained in al-Ghabisiyya until February 1949. During that month, there was a second expulsion, this time by the Military Government, on grounds of 'security, law and order.' It is not clear where the expelled villagers were taken.

After al-Ghabisiyya and its two neighboring villages of Shaykh Dannun and Shaykh Dawud were evacuated, the Israeli government permitted some of the inhabitants of the latter two villages to return to their homes. Those who had not sought refuge in Lebanon came back and were joined by a few families from al-Ghabisiyya, al-Nahr, al-Tall, Umm al-Faraj, Amqa, and Kuwaykat. The two small villages of Shaykh Dannun and Shaykh Dawud were merged to form a joint village called Shaykh Dannun; in 1973 it had a population of about 1,000. The village of al-Ghabisiyya, however, was not repopulated.

In 1950, Jewish immigrants from Iraq established the settlement of Netiv ha-Shayyara, 1.25 km west of the village site, on village land.

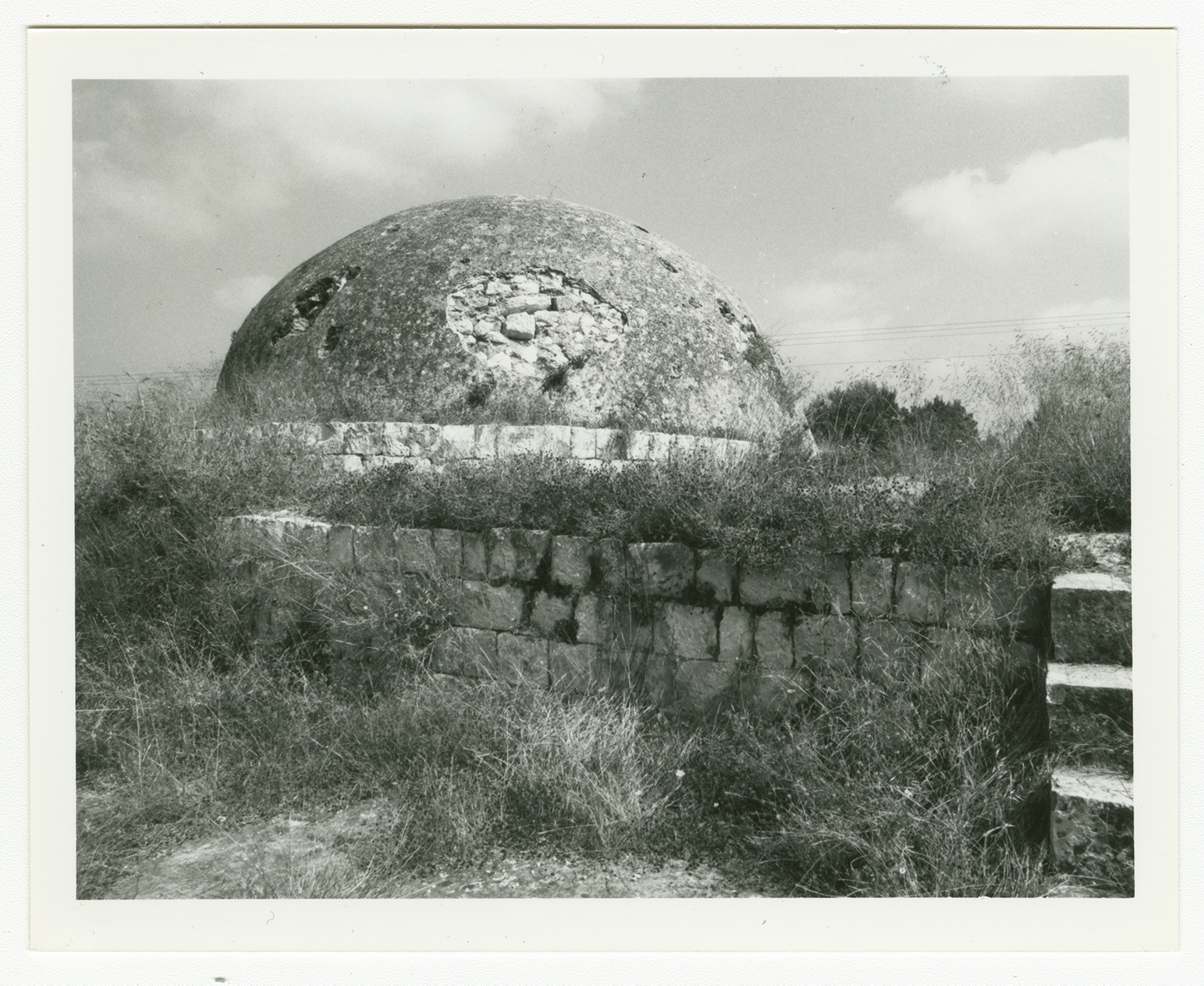

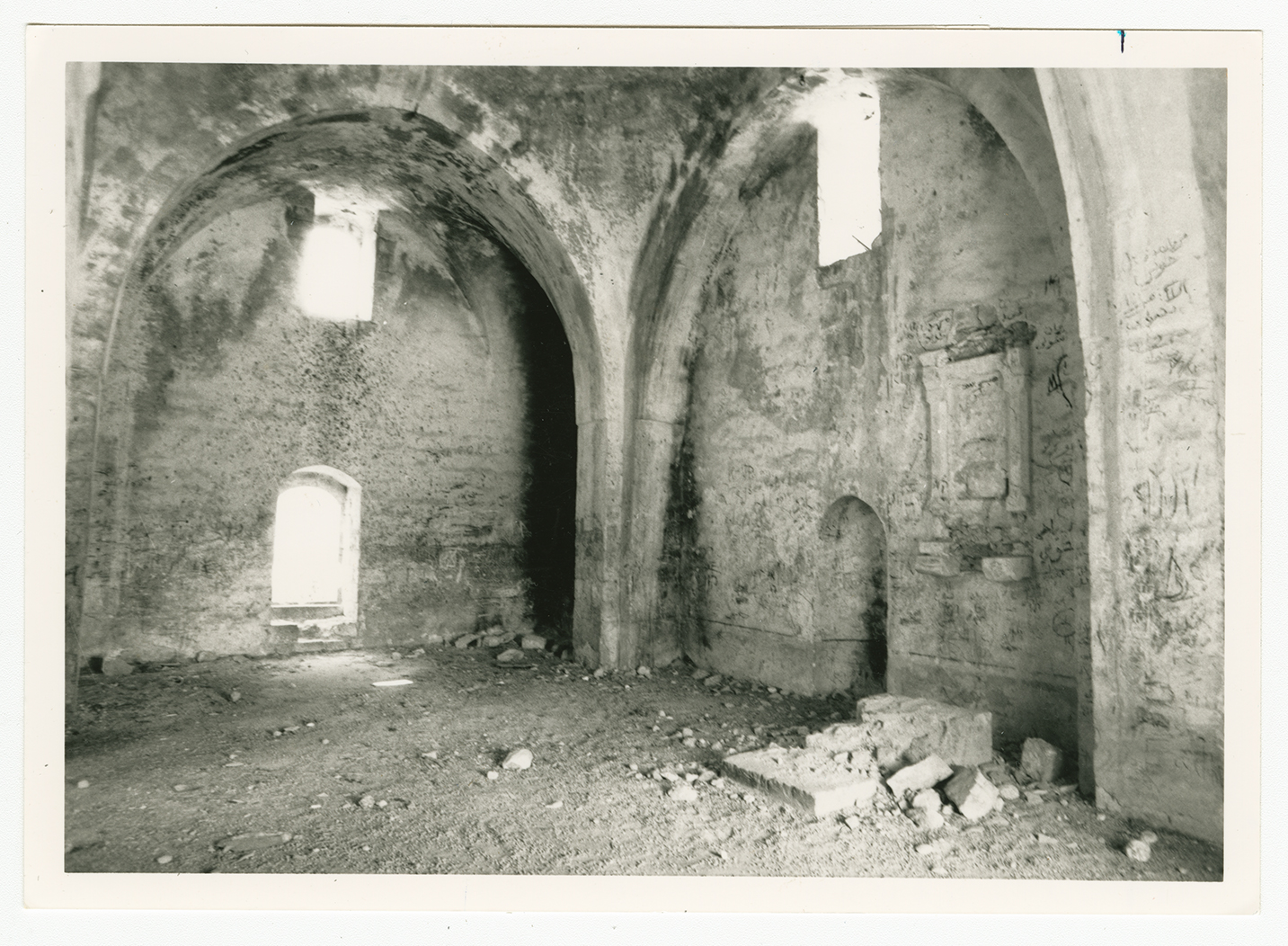

The only landmark that remains is the mosque—a domed, stone structure, with arched doors and windows and decorative arches in the interior. It is deserted, the cement plaster on the dome is peeling off, and wild shrubs cover the rest of the roof. The debris of houses, terraces, and the village cemetery can be seen amidst a thick forest of cypress trees that was planted on the village site and part of the land. Cactuses also grow on the site. The settlement of Netiv ha-Shayyara uses the adjacent non-forested land for agriculture.